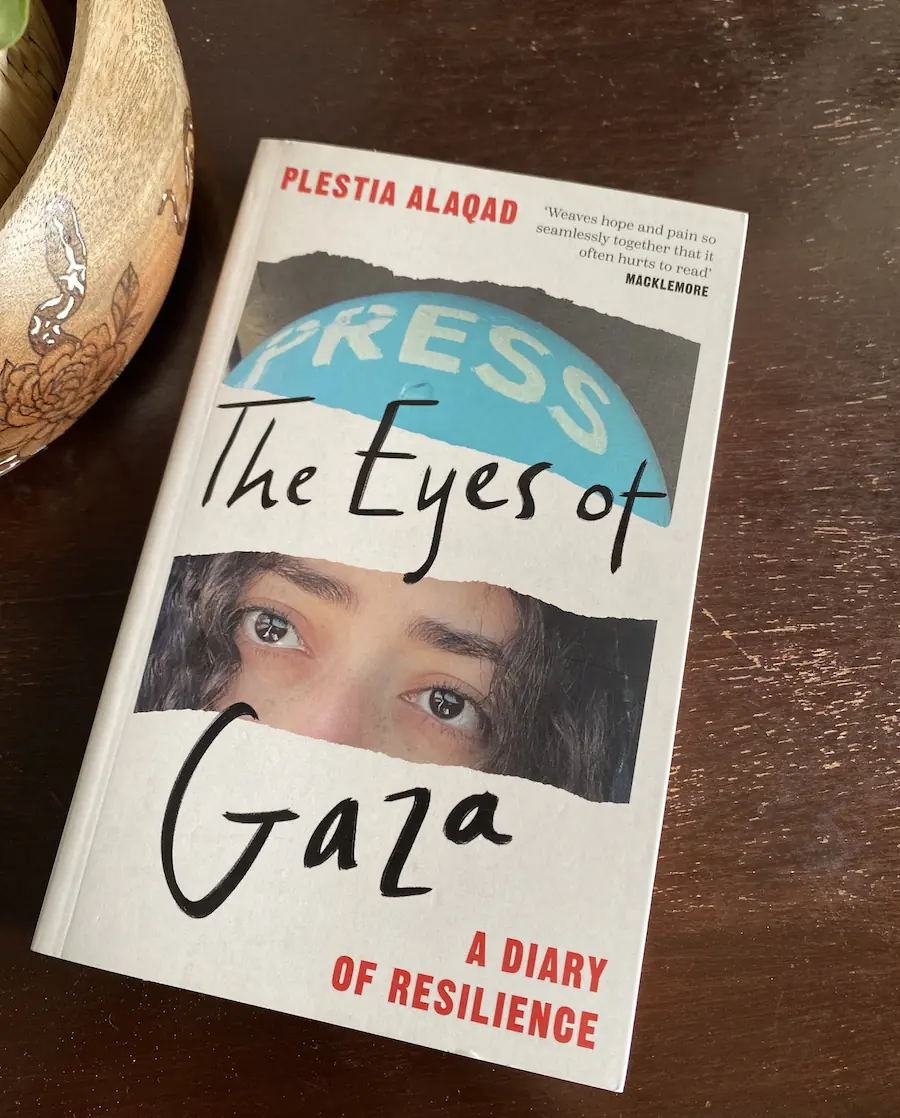

Review: Plestia Alaqad’s The Eyes of Gaza tells the heart-wrenching tale of living through a genocide

It seems fitting to share a review of The Eyes of Gaza: A Diary of Resilience by Palestinian journalist Plestia Alaqad on October 7, given that her novel is a compilation of her diary entries during her 45 days in Gaza under Israel’s intense bombardment. And though you would think after two years of seeing unending bloodshed and destruction on social media, one would be used to it, this book still had the power to make me cry.

It’s the kind of book that makes you wonder what you’d put in your emergency bag — your laptop, a hard drive, one pair of clothes, no books (too heavy), no photo albums, no trinkets, no jewellery — if your house was in danger of being bombed. If you had five minutes to clear out, what would you take?

This, Alaqad, says was the norm for Palestinians living in Gaza even before October 7, 2023. Her four-step emergency protocol — stocking up on groceries, a packed emergency bag by the door, windows cracked to help absorb shockwaves, mattresses dragged to rooms without windows — is described with a kind of indifference and acceptance that is shocking, not just because of what she’s describing, but because it’s portrayed as normal.

Before October 7, she met with her friends, went to a café, had tea with her mother and lived a ‘normal’ life. Nothing that followed was normal. The book is a series of diary entries by 21-year-old Alaqad, who had graduated from university but was still discovering what kind of journalist she wanted to be. Her place of birth decided that for her. Soon, Alaqad rose to fame for her reporting in Gaza, a young, frail girl almost drowning in a blue helmet and press vest.

The initial part of the book reminded me of a Karachi of years gone by — not at all in the intensity, but in the pretence that everything is fine when it’s not. When the world is on fire and she and her family laugh because her mother thought the sound of bombs dropping was the patter of raindrops, so she rushed out to get the clothes off the washing line.

That kind of affected indifference is so painfully easy to relate to for people who grew up in a city where targeted killings, attacks and bomb blasts were so common they became the butt of jokes — who can forget the infamous bori jokes that weren’t all that funny. Pakistanis too often laugh in situations where there is nothing left to do but cry.

One thing that struck me about The Eyes of Gaza was how it read in some ways like a dystopian novel. A world turned upside down, a young girl navigating it, her rush to get to hospitals and places with internet to tell her story. Her worry about her house being bombed while she was mid-shower — the kind of thing that seems inane but would worry me too.

But this was no fictional novel and the events were not a figment of someone’s imagination — this dystopian nightmare is a lived reality for the people of Gaza. The indifferent attitude she adopts is a coping mechanism for a life that is beyond what any of us can imagine.

“It’s better to be killed in daylight anyway; it makes it easier for paramedics to identify you,” writes Alaqad in one of her many musings on what she believes is her imminent death. It’s hard to see pictures and videos of death and destruction, but somehow, reading about the thoughts of someone in that situation is even harder. It’s not as graphic, but it punches you in the gut because you can easily picture yourself or your loved ones in this situation.

“I often think about all the children that the Israeli Occupation Forces have killed and who they could have grown up to be. Outstanding poets and bestselling authors who never had the chance to live. It saddens me to think of all the potential art that will now never see the light of day. The books that will never be read, paintings we will never get to behold.”

The repeated references to Israel’s attacks as “Aggressions” was interesting because aggression seems so tame a word to refer to what the Israeli regime was doing. But I suppose in a world where your people are being annihilated in a live-streamed genocide, “lighter” attacks could be called mere aggressions.

The Eyes of Gaza is the kind of book that you read with a tightness in your chest, bile rising in your throat and tears in your eyes. It’s a difficult read, not because of the language, but because the subject matter gets darker as you progress, and so does her voice. She starts off an average young adult — she uses Gen Z slang like low-key and rent free liberally and talks about things that only a young person would — but as the diaries progress, you can see the cloud forming above her, feel the desolation and hopelessness.

“Sometimes I wish that I’d just die, for the sake of resting in peace, and sometimes I wish to live, to one day see Palestine become free,” she writes, in a moment of reflection.

There are some things she writes that make you realise that the choice many Palestinians must make is a heart-wrenching one. Alaqad jokes with her colleagues — but it isn’t really a joke — that she doesn’t want to be saved if she’s burned or loses a limb. Her colleague muses that he could live without a foot. These would be the ordinary musings of a group of bored young people if it weren’t for the very real choice they may have to make if they do find each other’s bodies, buried amid the rubble of another bombed building.

On day 46, Alaqad and her family leave Gaza for Australia, and that’s when her survivor’s guilt kicks in. It was already there — she was aware of her privilege — when she felt guilty for being able to sleep on a sofa in her uncle’s home while others lived in tents, but it was magnified a thousand-fold when she left Gaza and was able to do mundane things like drink tea or take a shower.

Alaqad describes the surreal nature of living through a genocide and then going to a place where everything is ‘normal’ and it makes my heart ache for a young girl whose body was rescued but her mind is still in Gaza.

“I’m homesick for a home that no longer exists.”

Comments