5 things you should know about Moammar Rana's Azaadi

London-based journalist Zara (Sonya Hussyn) returns to her deceased father’s homeland Kashmir to tie up some loose ends of a personal matter.

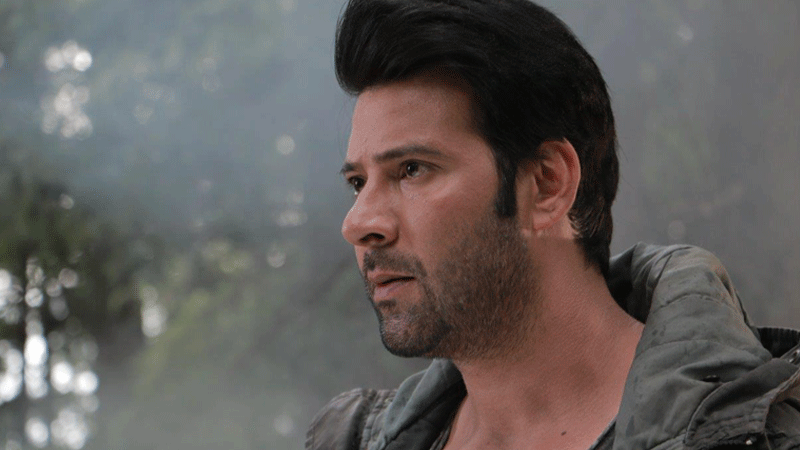

Except when she arrives at her uncle’s house, she learns his family has problems bigger than hers: having drawn the ire of the Indian army for his pro-independence activism, her uncle Baba (Nadeem Baig) saw his house raided and daughter raped some time ago. Tortured by this harrowing incident, his son Azad (Moammar Rana) left home to become India’s most feared freedom fighter.

So when Zara arrives in Kashmir, Azad decides she’s the only person he can trust to interview him for the international press. Zara takes up the offer. What revelations does Zara have about Kashmir’s struggle for independence through this interview? How does reuniting with her long-lost cousin change her personal equation with him? That’s the crux of Imran Malik’s Azaadi.

Azaadi is Imran’s directorial debut and has been jointly produced by him and brother Irfan Malik under the banner of their father Pervez Malik, most famous for directing Lollywood super-hits like Armaan and Doraha. Those are big shoes to fill. So how did Azaadi fare?

Here's five things to know about Azaadi before you watch it this Eid:

1) Don’t expect to learn anything new about Kashmir’s independence struggle in Azaadi

Azaadi makes an earnest attempt to highlight the plight of Kashmir and show that its people aren’t terrorists, as they are often referred to in international press, but freedom fighters. It tries to humanise those freedom fighters, show the men behind the warpaint and camo as well as the circumstances that forced them to pick up arms.

The film manages to do this, but the storytelling isn’t exactly stirring. As Zara arrives in Azad’s camp in the jungles of Kashmir, she hears the stories of his small band of men: Khalid the violinist who survives his village’s bombing, Dr Sikander whose mother is killed in a raid in retaliation of his treatment of a Kashmir independence leader, Riaz who loses his wife to gunfire from a lecherous Indian soldier. The film flashes back to present a montage of these instances of Indian oppression in Kashmir but the stories lose impact due to stilted dialogues and wooden acting.

Director Imran says Azaadi will provide “awareness [to the audience] about the Kashmir situation” but the script merely skims its surface, choosing to not go beyond the us-versus-them narrative. It portrays Indian politicians and forces as the embodiment of evil without probing the motivations India may have for its desire to occupy Kashmir. When it touches on the presence of ISIS in Kashmir, it reduces the appearance of its black flags at protests as an Indian ploy to confuse and divide the pro-Pakistan populace. On the flip side, Azad and his freedom fighters are shown to be motivated solely by a desire to defend and avenge.

Far from reflecting the changing and complex reality of Kashmir, the film serves to further the hate-mongering rhetoric that we’ve seen plenty of.

2) Azaadi also starts to make a point about marriage but then forgets

Azaadi is also touted as a love story and predictably, it’s Azad and Zara who do the falling in love. But there’s a catch.

[SPOILER] Zara is actually engaged to her boyfriend Raj. And a week before their wedding, she discovers that she was in fact married to her cousin Azad as a child, an event she doesn’t even remember. So her purpose of being in Kashmir is to actually ask him for a divorce.

Early in the film, much ado is made about the nikkahnama that declares her to be Azad’s wife. The film makes an important point about the legal consequences of a nikkahnama, that it is not a document that can be disregarded simply because it was signed many years ago.

However, what is not discussed is the legality of the nikkahnama itself given that Zara was a child when she signed it. And no one, not even Zara, brings up her lack of consent as an issue worth being talked about.

If the cavalier attitude towards consent was just a family-limited issue, it wouldn’t be as much of a concern. But Azaadi even brings a religious scholar into the mix, who urges Zara to reconsider her impending marriage to a Hindu man and celebrates the fact that her father arranged her nikkah to her cousin in childhood.

He parts with the note that some relationships make us stray from religion and we have to think about whether that’s worth it. (Never mind that a childhood marriage or a marriage without consent isn’t in keeping with religious teachings either.)

So, if there’s a point that the film tried to make about marriage, it’s that a Muslim’s marriage with a non-Muslim is kind of a no-no. [SPOILER] But even this message isn’t fully delivered because we never know whether Zara returns from Kashmir to marry Raj or not. So this part of the story isn't even resolved.

3) This is a war movie with bad shashkas

With jarring, jerky cinematography that can be kindly described as experimental but more accurately summed up as a really poor creative choice, Azaadi is a visual disappointment from the get-go.

And it doesn't improve. The fight choreography is a little like this: battle scenes take place without bloodshed, the bad guys always have terrible aim and Azad runs around toting a heavy machine gun without a bullet belt.

And then there's the lack of continuity, the obvious skimping on locations (our audience can tell Lahore and London apart) and the choppy sound design — Azaadi's no technical feat.

4) We’re still making problematic statements about rape

It’s 2018 and filmmakers and audiences alike are expected to be more sensitised to rape. Multiple movements have fought back against the myth that a person’s rape deprives them of their honour or is a source of shame. But clearly, the makers of Azaadi didn’t get that memo.

Rape is repeatedly associated with izzat in Azaadi and after his daughter is raped, Zara's uncle is unable to face her for and refers to her assault as an injury to the family honour. The fact that Zara is able to help father and daughter reconcile with their harrowing past is slightly redeeming and shows that a survivor of sexual assault is capable of psychological recovery and need not languish in solitude for the rest of their life.

5) Sonya Hussyn says her character Zara is empowering for women but we're not so sure

Zara is as much the film's protagonist as is Azad and she does merely feature as a love interest to him. Much of the film's plot is driven forward by her actions and that's refreshing.

But it's one thing to try to pen a strong female character and quite another to have the audience believe in her. Zara is a hot-shot journalist who had recently returned from a risky assignment in Iraq but still innocently asks a Kashmiri freedom fighter what he means when he says he has no family. Look around you, Zara. You're in a war zone.

Comments