Kavad Katha — the art of storytelling

While discussing the past in relation to art, one is often reminded of how T. S. Eliot has defined tradition in his remarkable essay Tradition and the Individual Talent. In a nutshell: he puts emphasis on the importance of the ‘historical sense’. This means: “The past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past.” But another important aspect of ‘the present directed by the past’ is looking back at one’s roots, simply because they provide the basis for our subsequent growth as a community.

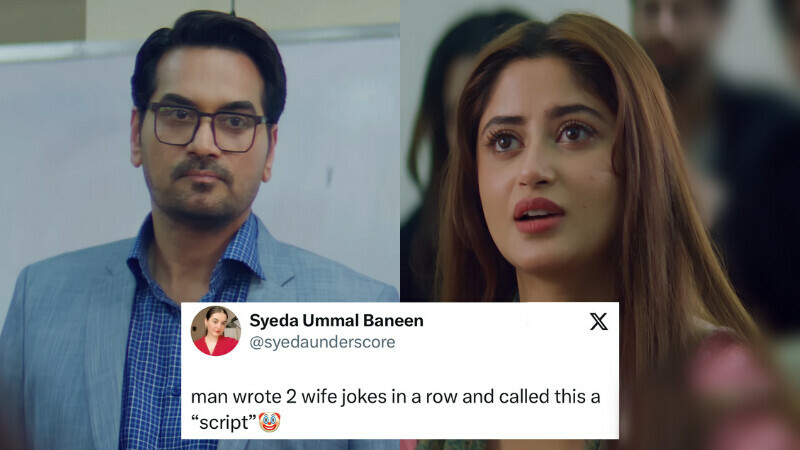

Directed by Rao Jamal Singh Rajput, Kavad Katha which premiered at the National Academy of Performing Arts (Napa) on Friday evening for a three-day run is also an attempt at revisiting one’s roots.

What kind of roots? Geographical? Spiritual? Physical? The answer is not as straightforward as one might think. Basically what Rajput has done is that he has taken an ancient Rajasthani form of storytelling — which used to travel to its adjoining areas in the old Rajputana region of India including that part which is now the province of Haryana — and employed Urdu, Sindhi and Haryanvi languages to tell the folk tales that are seldom told in our neck of the woods. One of the reasons for including Haryanvi is that both Rajasthani and Haryanvi dialects are a bit similar.

At the centre of it all, though, is the kavad katha, a three-dimensional form of narrating a story with a wooden plank that has doors painted with characters mentioned in the story. The doors are opened as the tale told by the kavadia (narrator) moves along; they’re accompanied by two musicians — sarangi and tabla players on Friday — on stage.

The show will continue till Sunday at Napa.

In the Napa production, Zubair Baloch uses Sindhi (Karonjhar Jo Qaidi), Hasnain Falak Urdu (Mirabai and Lord Krishna) and Rajput Haryanvi (Raja Amb and Rani Ambli) languages in their separate acts in a manner that can be categorised as lok dastangoi. After all, centuries back in the subcontinent, the oral form of kahani sunana was in vogue.

Rajput’s effort as a director should be commended primarily because his sense of history and profound admiration for it is strong. However, at the end of the day, theatre is an art form whose success depends on actors’ effective communication with the audience. With a script in which tradition is the mainstay of the plot, your main task on stage is not to let the art get upstaged by history. Both should be mutually reinforcing. In that context, Zubair Baloch’s performance among the three stands out. His voice projection gels with the mannerisms that he adopts for his act; and he seems to have a knack of knowing how to wait for the music to begin or end to enhance his presence as a kavadia.

Well done.

Header image: A scene from the play. — Shakil Adil / White Star

Originally published in Dawn, January 13th, 2024