Pakistani actors and royalties: A royal mess

Veteran Pakistani actors recall a time in the early ’90s when a single state-owned TV channel ruled the roost. Pakistan Television Network (PTV) wielded immense power as the main source of revenue for a burgeoning fraternity of actors, writers, directors, producers and technicians. At the same time, the channel was dependent on these artists for its content, and knowing this, a large contingent of them had decided to go on strike.

Their wages were far too minuscule, the artists had argued, and they wanted a raise. It’s remembered that PTV eventually complied, giving them raises but eliminating the royalties that they were paid for re-runs of their work.

Royalties, or residuals, refer to the payments made to artists when a project that they have worked on gets re-run. In the global television and cinematic industries, these payments are extended to the producer, director, writer, the primary cast and other technicians who may have played significant roles in the creation of a project.

Remunerations are calculated according to a pre-determined format, and tend to get reduced with every re-run. Generally, by the time a project is re-run a certain number of times, the royalty payment gets reduced to a minimum, which then gets paid for every further re-run. These payments may be limited to a certain time period — 10 or 20 years — or may even go on forever. The amounts also vary from one medium to the other. For example, a different pay may be allotted for re-runs on TV, for DVD sales, streaming on OTT platforms and YouTube views.

A video by an ailing actor has brought the issue of the lack of royalty payments back into the spotlight in Pakistan. But Pakistan’s artist community is caught in a Catch-22. Individual artists risk being blackballed by channels if they raise a voice for their rights. To get anywhere, they must all stand together. Can they?

Royalty payments on re-runs of a hit show could easily reap millions for its leading cast and creators. Consider a show as hugely successful as NBC’s Friends, and how it has been aired repetitively on hundreds of channels around the world. Regular paychecks for every re-run can mean a constant outpouring of revenue.

Unfortunately, when Pakistan’s artist fraternity decided to forego royalty payments without making a hue and cry, it didn’t realise that it was letting go of a sum that could be paid to them long after a project had wrapped up.

Actor Khaled Anam recounts, “Suddenly, everyone was earning much more and they didn’t realise that they had lost out on payments that they could have availed for many, many years.”

Actress Samina Peerzada similarly observes, “At that time, we didn’t realise how the Pakistani TV industry would mushroom in a matter of years. Satellite channels and digital platforms emerged and, suddenly, we were losing out on a large chunk of residual payments. We were being paid a single time in Pakistani rupees for content which was getting aired multiple times around the world, and generating constant revenue for whoever had purchased it. This needs to change now. It’s a different world and artists have a right to be paid royalties for their hard work.”

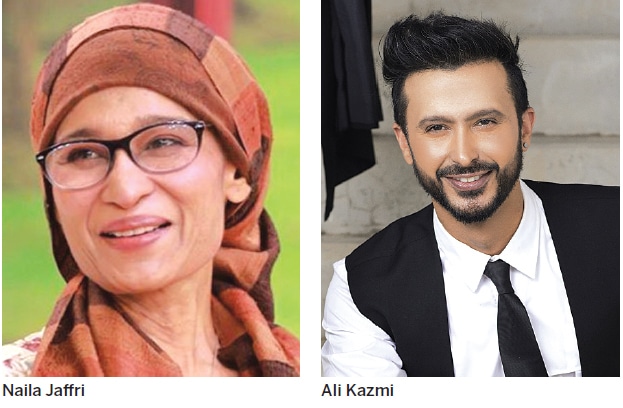

Samina’s views form the gist of a complaint that has sporadically been voiced by the Pakistani TV and film industry, but to no avail. Recently, the issue came to light once again when ailing actress Naila Jaffri released a video on social media.

Battling cancer for the past six years, Naila spoke from her hospital bed and said that it would be a great help for people like her and their mounting expenses if artists were paid royalties for their work that continued to re-run on TV and online platforms. “Perhaps the decision to grant royalties may not be made overnight. Probably, I won’t be able to avail these payments. But I am hoping that I have triggered off a change that could benefit the future generation of artists,” Naila told Icon.

“An artist doesn’t have to be ill or impoverished to be paid royalty payments,” points out actress Bushra Ansari. “If Robert de Niro gets paid royalties on his work, does that mean that he is needy? It’s our right to be paid royalties for the work that we do. In the earlier years, PTV followed the format of the British Broadcasting Corporation [BBC] and paid us a very small token amount every time our acting projects were re-run. It may not have been much, but it still followed basic principles.”

“Why should we even need to ask for royalties?” questions Samina Peerzada. “It’s our right. Why do we have to resort to being beggars in our own country?”

Actor Ali Kazmi observes that he gets regular royalty payments for his work abroad — unless his contract includes a ‘buy-off’ clause, where he would be paid a single time for his work — but none for his work in Pakistan.

Satellite channels and digital platforms emerged and, suddenly, we were losing out on a large chunk of residual payments. We were being paid a single time in Pakistani rupees for content which was getting aired multiple times around the world, and generating constant revenue for whoever had purchased it. This needs to change now. It’s a different world and artists have a right to be paid royalties for their hard work,” says Samina Peerzada

“The royalty payment may be very little, but it is still there. I don’t even have to keep track of it. It is sent to me because it is my right to get it. Meanwhile, in Pakistan, I’m aware that my dramas such as Jackson Heights and Baaghi are constantly getting re-aired. Some of them have run on Indian platforms such as Zee Zindagi and Zee5 multiple times. But we, the artists, don’t gain anything from them.”

Cracks running deep

However, the complete lack of residual payments in Pakistan is merely one of the problems faced by the artist community. Actress Rubina Ashraf recalls instances when junior artists didn’t get paid their minuscule salaries for years by TV channels.

Ali Kazmi feels there is a need for institutes that offer training and degrees in the technical and legal aspects of entertainment-related genres, ensuring greater respect and recognition of the industry. “Private living room conversations in the industry often focus on how some of today’s most famed TV producers are owed billions by channels. The producers may have churned out multiple hit dramas, but these are bought out by channels that only pay them after two or more years.”

Actor Ahmed Ali Butt points out that the TV and film industry isn’t even recognised as a proper profession by the state. “My profession falls into the ‘Others’ category on my national ID card. I stand by my community in the demand for royalties, but how can we expect fair treatment when we aren’t even given the status of established professionals by the state?”

“It’s sad that in Pakistan there is no respect or value for the soft image ambassadors that represent the country to the entire world,” laments actress Atiqa Odho.

Royalties, then, is only one amongst many issues. It is, however, under scrutiny right now following Naila Jaffri’s video. And actor Mikaal Zulfiqar, who has also been quite vocal on the topic in the past, says that it’s an issue that needs to be tackled immediately.

In February this year, Mikaal had posted an image of his drama Diyar-i-Dil on his Instagram, stating that Hum TV Pakistan was airing the drama “for the umpteenth time”, adding, “If only we got paid for re-runs. Would never have to work another day in life.”

“Consider the extent to which a channel earns once a project has been purchased by them,” says Mikaal. “We get paid for working in it once and, then, revenue is earned by them through advertisements on TV, advertisements on the YouTube uploads of the drama, re-runs within Pakistan as well as abroad. So many of our dramas get dubbed into foreign languages, and are then aired in different parts of the world. Zee Zindagi, in India, airs our dramas constantly and many of them are even available as ‘In-Flight Entertainment’ in airlines. But the cast and crew, whose creative efforts were invested into the drama, don’t get anything out of this.

“I asked MD Productions [the production house responsible for a large fraction of the content aired on the Hum TV Network] for royalties once,” says Mikaal. “I was told that we don’t pay royalties. And naturally, taking a stand on my own would have only led to me not getting any work. Any such demands need to be made collectively.”

This is the Catch-22 faced by Pakistan’s artist community. The TV and film industry in Pakistan hasn’t been paid royalties for nearly three decades now and channels, unless pressurised, would hardly want to damage their profits by beginning to pay them now. An artist demanding that his or her contract include a clause ensuring royalties runs the risk of simply getting sidelined by the channel heads. Other artists, not insisting on these requirements, will be hired instead.

“At the end of the day, artists needs jobs,” says actress Atiqa Odho. “How many of them will be willing to sacrifice their bread and butter in order to take a stand for the community as a whole? Unless they all collectively stand together, no change can take place.”

United, we stand

Producer Wajahat Rauf voices similar concerns. “The entire artist fraternity, and not just the actors, need to be united in their demands for royalty payments,” he says. “I feel that independent producers suffer the most because we pay our cast and crew from our own pockets, sell the drama to a channel and, then, wait for the payment to filter down in a span of years. All channels have in-house production teams also, which means that the work of independent producers rarely gets prioritised. If a single producer starts demanding royalties, he will just get blackballed. But if everyone stands together, we can bring about change.”

He continues, “Once we have sold the drama, it ceases to be our property altogether. If producers were paid royalties on the many times their work was re-aired, we would be able to distribute them further amongst the artists who have worked with us on the project.”

One of the key steps towards the re-acquisition of royalties is the drafting of legislation that highlights the details according to which remuneration needs to be granted. The onus of this is likely to fall on the Actors’ Collective Trust (ACT), a federally registered body representing Pakistan’s actor fraternity.

The General Secretary of ACT, actor Omair Rana, elaborates: “ACT takes the issue of royalties very seriously. We had been addressing the need for them earlier as well, but I’m glad that Naila Jaffri’s video has helped our cause gain traction. We’ve seen a surge in members joining into the Trust. Perhaps more and more artists are now realising that, unless they look out for themselves and demand their rights, they might also one day face the same problems as Naila. We work in association with the government and have lawyers on board, and we’re trying to get all stakeholders on board — producers, writers, composers, actors, directors and even the broadcasters.

“The struggle for royalty payments doesn’t have to become a fight of us vs. them [the artists vs. the channels and broadcasters]. In the long run, these payments can actually benefit everyone.

“If artists know that they will gain profits from a project in the long run, they will work harder on it,” explains Omair. “They will invest more in its technical resources which will, ultimately, make it a more exportable end-product. Actors will feel less insecure and may not feel the need to work in two to three projects simultaneously. By focusing on a single project at a time, they will perform better and the management of the entire production will be far more efficient.

“Everyone will just work with greater enthusiasm and commitment. The broadcasters gain massive profits from re-runs, and they may have to share these with the artists but, then, more people will want to work with them because of their fair and ethical practices. The investment will eventually return to them, multifold.”

No country for residuals

Omair’s reasoning doesn’t hold much weight with the broadcasters. Re-runs don’t always culminate in massive profits, sources within major private channels argue. Multiple off-the-record conversations with media personnel working in private channels reveal that channels feel that artists get paid hefty amounts in lieu of their work already. Many of them even charge substantially for making appearances in talk shows and game shows taking place in a channel.

“They aren’t as badly off as they portray themselves to be,” argues a channel executive who did not want to be identified. “Pakistani dramas may be re-run worldwide, but the international audience is limited, easily getting diverted towards Indian content. There is a cost borne by channels for broadcasting internationally while the money earned from subscriptions is limited. Yes, we earn through ads on YouTube, but a percentage of this is allocated to Google. The ads that we may have been getting on TV just get diverted to YouTube. Also, dramas are sold off for in-flight entertainment at minimal cost. They add prestige value to our channel but they don’t really make profits for us.”

Khaled Anam observes, “The government needs to step in, because a decision will never be reached if artists and channels just keep arguing against each other.”

To this end, some recent statements by PTI Senator Faisal Javed Khan have made the artist community feel hopeful. In a series of tweets, the senator stated that it was “very critical to fill the gaps and bring proper framework via amendments in legislation to ensure that our producers [and] artists get their rights to royalties. Am in touch with all stakeholders and [Inshallah] a comprehensive bill is being brought soon to address this very important issue.”

“I feel the pain that the artists go through,” says the Senator. “I’m hoping to get a bill passed along lines that will protect their rights and ensure more security for them. We’re going to be looking at international laws regarding royalties and adapting them to a Pakistani model.”

This ‘Pakistani model’, one assumes, will take note of the limitations of the local audience and the struggles of channels as well as the artists. Ultimately, the fraction set aside for royalties may not be a sizeable one. It would, nevertheless, be a step in the right direction and may make artists feel less marginalised and more secure in their careers.

With the government taking notice of the artists’ plight, there is a chance that a turnaround truly may take place in the Pakistani entertainment industry. What is essential, though, is that the artist community stands together and not get swayed by friendships and allegiances forged with particular channels.

It is also noticeable that, while some artists may be raising their voices, there are other, very popular ones, who have remained quiet. More of Pakistan’s top tier artists, with enough fan followings to ensure that their every project is a hit, need to start speaking out. If they insist on royalty clauses being added to their contracts, channels may have no choice but to agree. The future progress of an entire industry may depend on them.

Originally published in Dawn, ICON, April 18th, 2021

Comments