Women are battling a spike in online threats after the Aurat March, but does anybody care?

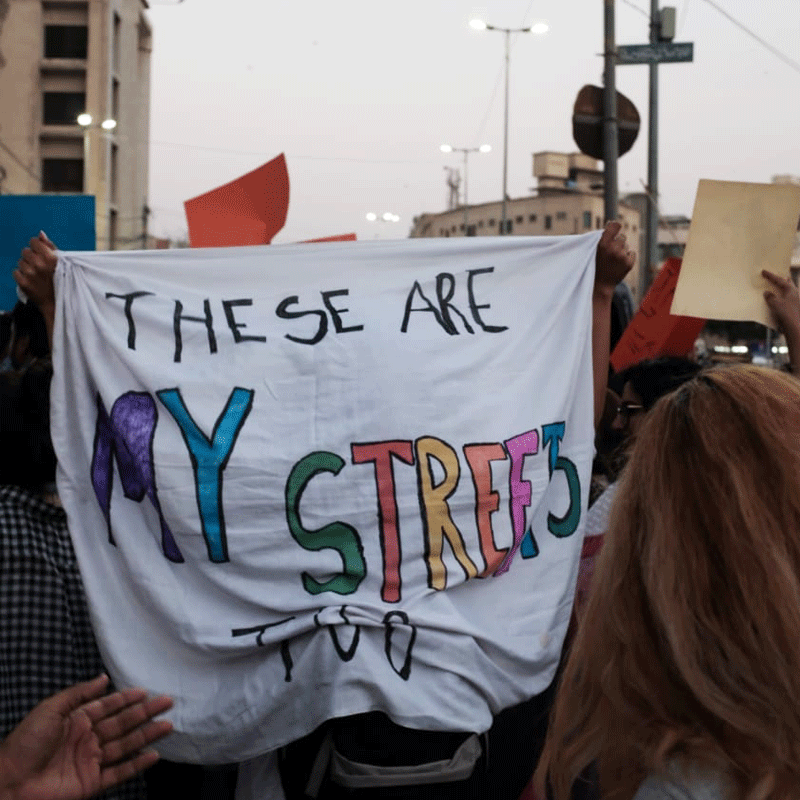

On March 8, women across the country – from Hunza to Hyderabad and Karachi – organised marches in order to reclaim public space, express their freedom to express themselves and fight the patriarchy.

However, the backlash against the Aurat March and its organisers was swift. The backlash began with a trickle of comments on Twitter and Facebook, then escalated as people began faking and doctoring images of posters to circulate them on social media and stir up further controversy.

Read: Lahore's Aurat March sends a strong message against patriarchy

The backlash moved to mainstream media, and then to legislative assemblies, with lawmakers threatening action against the women who organised the marches.

And then came the threats. Women who attended the marches say they have been suffering online bullying, harassment, and even rape threats. The march's organisers have fared worse, forcing many to limit their activity on social media for a time.

In Pakistan, this qualifies as a crime according to the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016. This specifically looks at offences against the dignity of an individual, i.e. sharing doctored images, fake profiles, hate speech, blackmail, harassment, stalking, revenge porn and other offences. If convicted, an individual can be sent to prison and fined as well. However, this hasn't stopped the spate of hate.

Last week film student Javaria Waseem tweeted about her sister’s experience with online harassment following the Aurat March. “I have a 16 year old sister who posted on her Instagram supporting the Aurat March and a random group of boys made a group just to abuse and harass her, calling her names and talking about doing sh*t with her. SHE IS JUST SIXTEEN,” said Javaria in a Twitter thread that included screenshots of abusive messages her sister had allegedly received online.

Speaking to Images about the incident, Javaria's sister says: "Not only did they abuse me... but they shared my ID and one of them even talked about giving my number to anyone who wanted it. I decided to share everything on my Instagram story to expose them publicly, thinking they might feel ashamed but all they cared about was losing their followers. The stories triggered them and led them to abuse my parents, my family and one of them even told me to play the blue whale game and die as I’m ‘biological waste’."

“They called me everything from a mental patient to a wh*re. They shared my pictures in their group to make fun of me and multiple times they even used phrases that pointed towards raping me," she continues.

Journalist Manal Khan made a poster which read ‘Mein Awara, Mein Badchalan’ and became a meme within hours. The situation escalated when trolls doctored her posters and made them inappropriate. Some went as far as to compare her to a porn star. "It did not bug me unless my photograph was edited. What started annoying me is when they photoshopped my poster into other things," she says.

Lawyer and digital rights activist Nighat Dad, who is one of several women who organised the march in Lahore, said that she also faced harassment online following the march.

In a photograph taken at the march, Nighat Dad can be seen with two other women holding a poster which reads: “Divorced and happy”. Many accused her of interfering with 'culture' by 'encouraging' women to leave their families and upsetting the traditional Pakistani household. This response, however, was tame compared to the rape threats and 'd*ck pics' she says she received in her DMs.

So what can a person do when faced with similar cases of online harassment?

Seeing swift action on reported cases of cyber bullying is still a pipe dream for most

Speaking of her own case, Nighat Dad says: “I took a screenshot of the rape threat I got in my inbox and tweeted it and reported the man to Twitter. Along with this I filed a complaint with the Federal Investigation Agency’s cybercrime cell."

Additionally, she says, the Digital Rights Foundation (DRF), a non-profit led by herself, has been receiving complaints of cyber bullying and harassment on their helpline.

“People who organised the marches have been receiving threats and have been passing on the information to us. We are talking to these women individually. There are photoshopped images of these women doing the rounds on social media and WhatsApp. We are currently in the process of asking Facebook to take these down via our escalation channel with them," says Nighat.

So far, she adds, no woman who has approached DRF wants to lodge a complaint with the FIA.

“The FIA can only take action when someone files a complaint with them. However, the FIA claims that it can also take action on their own as well. But so far they haven’t done anything against MNA Aamir Liaquat or talk show host Orya Maqbool Jan [who have gone on record to denounce the Aurat March]. Things that have been said by these men and others – they are technically committing a crime under the cybercrime act. I would encourage women who are facing rape, death threats and hate speech to file a complaint immediately under the prevention of electronic crimes act,” she says.

In light of the online harassment post-Aurat March, Nighat says that her organisation has spoken to the FIA and aims to submit a collective complaint against accounts inciting violence against women marchers/organisers and sending them rape/death threats. “Women can inbox me screenshots of hate speech and rape threats and their URLs from Twitter, Facebook and Instagram,” she adds.

Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi, an organisation that champions internet privacy and free speech in Pakistan, says that the FIA should act on complaints of harassment and abuse. “What is spread on social media falls under the FIA’s domain. With respect to what Aamir Liaquat, Orya Maqbool and the MNA said, that is being countered with more speech and rebuttals. Cyber crime complaints with FIA can be lodged online via complaint form or by visiting in person,” she explains.

“I don't believe in lodging criminal complaints for speech unless of course someone's safety is threatened - and we know in many instances it has been - so in those cases authorities need to respond to complaints. Especially those threatening violence,” she adds.

For their part, a representative of the FIA cybercrime cell Abdul Ghaffar says the body has not received any complaints from women about post-Aurat March backlash as yet.

Discussing this situation, international public policy and gender reforms specialist Salman Sufi says that violence against women has evolved into new forms given the introduction of social media.

“The sadistic pleasure of trolling and harassing women online reveals the cowardice of the person on the keyboard. Yet that cowardice takes a real toll on the recipient’s mental and physical health. Mere shout outs against violence against women won’t do anymore, strategic policy driven implementation mechanisms should be adopted,” he says.

He adds that government-run violence against women centres built in Multan offer help to victims of not only domestic abuse but cyber harassment as well, where extreme cases of harassment have affected the victims psychologically. “They can receive free therapy as well as shelter if needed. The Punjab Women Protection Act has a clause for protection order that I specifically added to ensure that perpetrators can be ordered to stay away from victim and can be monitored with electronic bracelets,” he adds.

So far, the women who have experienced this online harassment feel they have no recourse except to turn to the very medium they received threats on, that is, social media.

As Javaria's 16 year old sister says: "There were a few people.... who told me not to upload stories or to simply ignore the harassment as it apparently ruined my reputation. They said that none of these guys would ever actually take this whole situation seriously. And they didn’t until my sister shared the whole situation on social media and decided to deal with it according to the law."

Complaints related to cyber crimes can be reported to the Federal Investigation Agency here.

Comments