Our barbed boundaries: Who's losing what as Pakistan-India wind up cultural exchange?

In late September this year, Mumbai’s biggest studio Film City was searched by an incensed crowd. They were looking for Pakistani actor Fawad Khan, apparently because he belonged to the ‘terrorist state’ of Pakistan. Uri, in Indian-held Kashmir, had been attacked and 19 Indian soldiers had died. Pakistan was to be blamed and all Pakistani actors working in Bollywood needed to be kicked out of India, pronto.

Art had no boundaries, people had proclaimed time and again, when Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Strings, Shafqat Amanat Ali and Atif Aslam had topped the Indian music charts. They nodded approvingly when Pakistanis further came into the spotlight in mainstream Bollywood. Ali Zafar rode into India, Fawad Khan swept through Bollywood, Mahira Khan signed up as King Khan’s leading lady and a burgeoning mass of Pakistani actors set their sights upon India’s lucrative silver screen. All these people are biting their tongues now.

When it comes to India and Pakistan, art certainly has boundaries; barbed sharp-edged ones which are not uncrossable but can tear those trying into shreds.

The activists, probably members of Maharashtra Navnirman Sena party, did not find Fawad at Film City because the actor had long wrapped up work for his latest Bollywood project and returned back home in July. But they reflected a semblance of the ire that soon began to pour out from Indian media and Bollywood itself. Shortly thereafter, the Indian Motion Picture Producers Association passed a resolution that barred Pakistani artists from working in India.

Pakistani actors were invited to sign on to projects in India. They may have stood to gain from the extensive platform and finances but they also invested their time and efforts into the movies. There’s no reason for Bollywood to suddenly clamber on to a high horse when, so far, their associations with Pakistani actors have been mutually beneficial.

The Indian film fraternity promptly divided and continues to make headlines as more and more artists voice their opinions. Some, such as Karan Johar, Salman Khan, Om Puri and more recently film-maker Anurag Kashyap, have objected to cinema being made a political scapegoat when all other trade between India and Pakistan continues normally. There are others — Anupam Kher, Ajay Devgan, Akshay Kumar, Farah Khan and Sajid Khan among them — who feel riled by the death of their jawans and have asserted that Pakistanis no longer have a place to work on their territory.

Anupam Kher held that, as a sign of goodwill, the Pakistani contingent could at least condemn the Uri attack just as he had condemned the Peshawar attack in the past. But when was India ever blamed for having orchestrated the massacre in Peshawar? How could Pakistani actors condemn an act of violence for which their own country was being blamed? In addition, the attack took place on soldiers in Kashmir, a territory Pakistan does not accept as India’s. It would have been deemed unpatriotic of them and moreover, rendered them in danger of being vilified once they returned to their home-base.

Instead, Fawad Khan and Mahira Khan posted public Facebook messages where they talked of peace. But diplomatic, carefully worded messages are hardly ever enough to stop vitriol stemming from a history of contention.

The hashtag #banPakartists continues to run rampant on Twitter and news that doesn’t make much sense filters through every now and then. For instance, the suggestion that Fawad Khan’s character in Karan Johar’s latest Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (ADHM) was going to be replaced by Saif Ali Khan was entirely implausible. The movie has been getting considerable flak for featuring a Pakistani and has been running the risk of being pulled from some theatres in India. However, given that the news came through a mere two weeks prior to the movie’s release, it would have been technically impossible for the actors to be replaced.

The social media censuring has, however, managed to pummel Karan Johar into making a public statement that of course, in the current circumstances, he won’t ‘engage with talent from the neighboring country’ any time soon. His cross-border friendship with Fawad Khan and talk of artistic freedom can bite the dust for now — not when his movie could incur losses by getting banned through half of India.

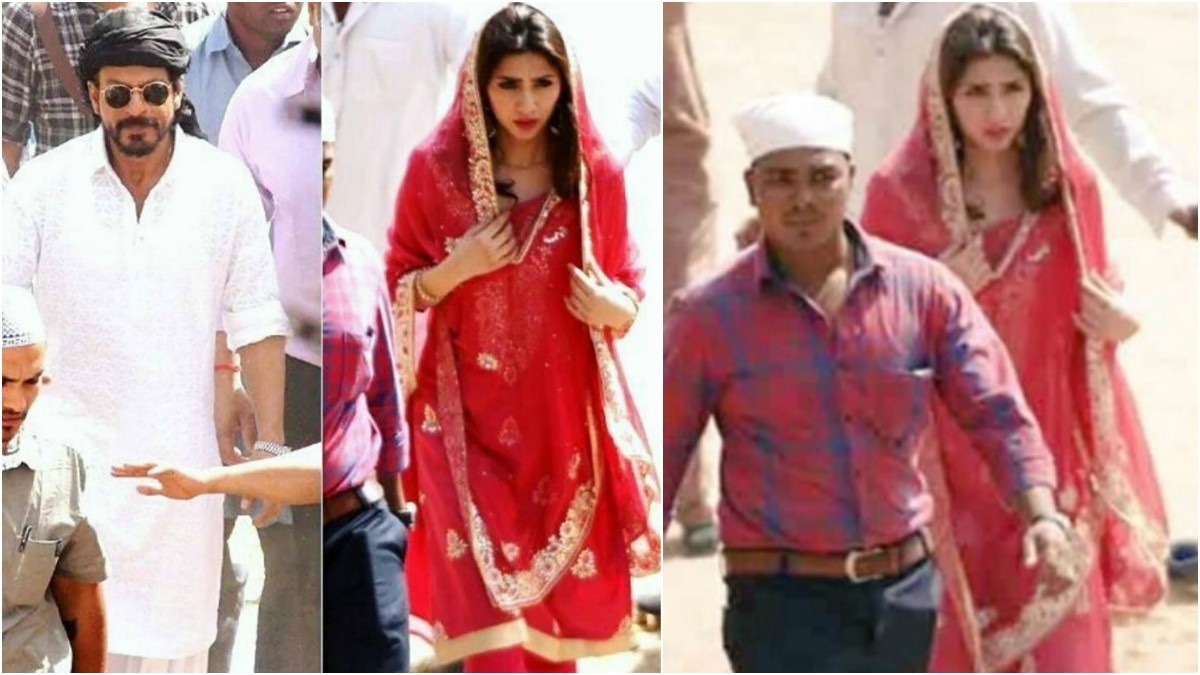

Yet another piece of propaganda came proclaiming that Mahira Khan’s role in the Shah Rukh Khan-starrer Raees, set to release in January 2017, was going to be now taken on by another actress. It left the movie’s director Ritesh Sidhwani flummoxed, prompting him to state that he ‘didn’t know where the rumours were coming from’ since he had ‘already shot with the girl for 45 days and finished the film.’ Could Ritesh also soon suffer a change of heart a la the fickle Mr Johar? One wouldn’t be surprised — that’s just how ridiculous Indo-Pak cross-border tension can get.

In other news, Ali Zafar’s appearances in the trailer of Dear Zindagi, releasing this November and co-starring SRK and Alia Bhatt, have speedily been cut out. Will his scenes also be reduced in the movie? Possibly, probably.

Needless to say, cross-border trade shows such as Aalishan Pakistan and Shan-e-Pakistan have also gotten postponed.

Given the tumultuous history between India and Pakistan, it had seemed unbelievable when Pakistani actors had, for the first time, become household Bollywood names. It is, however, quite believable — and inevitable — that they couldn’t possibly have lasted the long haul in India.

Politics meet sour grapes

One wonders, though, if the wave of patriotism currently engulfing Bollywood’s actors suggests a classic case of sour grapes?

“Women are willing to jump down from the rooftops for Fawad Khan,” Shoojit Sircar, director of Piku and producer of the recent Pink had commented some time before the Uri attacks in an exclusive interview with Images on Sunday. His leading lady in Pink, the young, very promising Tapsee Pannu, had declared that the hero she really wanted to work with was Fawad Khan. “The ADHM trailer has just come out and he completely dominates in it. All the other stars just fade out,” she had enthused.

It would only be natural for the Indian fraternity to feel irked by Fawad, who had happily sauntered where no Pakistani had managed to tread before. In a matter of just a few years, he had gotten colossally popular in India, signed on big projects, been featured on umpteen magazine covers, gotten rave reviews not just for his movies but also for his Pakistani TV dramas aired on the Zindagi channel, hosted the IIFA awards, won a Filmfare by beating star-son Tiger Shroff, and boasted a huge besotted female fan following. Why wouldn’t they want him to go, giving up on the accolades and projects that belonged to ‘their’ country?

Similarly, playing leading lady to SRK is a coveted slot and quite a few egos must have gotten wounded when Mahira Khan had crossed borders and slipped into the role.

“Dear Fawad Khan. It’s time. Go back to Pakistan,” an Indian journalist had written in an online letter, shortly after the Kashmir debacle, talking about how India had given him “more money in two years than what he could have earned in Pakistan in 10 years.”

But Fawad’s acting trysts in India have spelt box office success for his products as well. It’s a known fact that Pakistani actors charge lesser than their Indian counterparts and Fawad’s considerable acting skills, good looks and on-screen magnetism have been an impetus in making his Indian projects a hit. This was probably why Karan Johar chose to feature the actor in ADHM. Had the political climate remained stable, Fawad would possibly have been the highlight of the movie.

Tit for tat — but does it make sense?

As the situation snowballed, cinema owners in Pakistan made a call of their own and decided to restrict the screening of Bollywood movies until tensions abated. “As a nation, we felt very hurt by what was happening, which is why we chose to voluntarily shut down Indian movies for some time,” explains Jamil Baig, the area coordinator for Nueplex Cinemas.

Humayun Saeed points out, “At some point in the future, when we have a thousand cinemas and are churning out hundreds of movies a year, Bollywood will get eliminated from our screens on its own.”

Mr Baig and his peers helming the rebirth of cinemas in Pakistan must have expected that matters would improve in a few days. Now that tensions continue to prolong, they’re probably feeling dismayed. Cinemas need a new movie every weekend in order to keep finances rolling and this content is provided to some extent by Hollywood but to a much larger extent, by mass-centric Indian movies. The 10 or 12 movies currently being produced by Pakistan’s nascent film industry simply don’t suffice.

As actor and producer Humayun Saeed points out, “Our cinemas will end up shutting down or, at least, new screens won’t be put up. This isn’t the time to shut down Bollywood because we need to build more cinemas and have more investors enter the industry. At some point in the future, when we have a thousand cinemas — rather than a mere 90 — and are churning out hundreds of movies a year, Bollywood will get eliminated from our screens on its own.”

“Additionally, competition from Bollywood movies encourages our film-makers to maintain standards with their own projects. Personally, nobody would benefit more than me should Bollywood remain banned. My movies would release and become all-out hits due to utter lack of competition. But I am looking at the bigger picture right now.”

On that note, director Wajahat Rauf is probably one of the happiest film-makers around at the moment. His Lahore Se Aagey releases on November 11 and should the ban persist, he’s bound to hit box office gold. The one possible spanner in the works: there’s a chance that ADHM will release in Pakistan, on the basis that it features a local actor, and will proceed to pave the way for Indian movies to return to our screens again. It makes economic sense, if not patriotic. But perhaps this is a time when business concerns should be given precedence over emotion?

“It all depends on whether relations deteriorate or improve,” surmises a glum Jamil Baig.

Fire fire!

But are relations really improving when every day, yet another Indian celebrity jumps on to the ‘ban Pakistan’ bandwagon?

About two years ago, Ali Zafar had announced that he was going to focus more on his market in Pakistan. One assumed that this was because he wasn’t being offered promising work from India but perhaps Ali was on the right track after all. He has been visible at umpteen local ceremonies and is set to begin shooting his debut movie in Pakistan with director Ahsan Rahim.

In contrast, actress Mahira Khan gave up on a range of meaty roles in Pakistan simply because her time was taken up with Raees’ shooting. According to an inside source, right before the Uri debacle, she had expected to leave for India because certain scenes of hers in Raees were to be extended. These scenes never did get shot once all hell broke loose.

Adnan Sami Khan — once a Pakistani, now an Indian — presented his own twisted logic to the scenario. According to him, if one visited a neighbor’s home and the home caught fire, one needed to help and sympathise with the neighbor rather than run away and take cover. But what if the said neighbor accused one of having set the fire? What can Pakistani actors do when they are slandered when all they were doing was their work?

India, while an exciting option, will always be a volatile terrain for our actors. They may pursue cross-border work but it is unfeasible to make it the pivotal part of their careers. Similarly, Bollywood film-makers may find Pakistani actors interesting because of the novelty — and lower fees — they offer, but their movies run the risk of being slammed unceremoniously should political tensions suddenly arise.

Beyond art and cultural exchange, the Indo-Pak border flickers with flames. It simmers, burns and sometimes kindles into a roaring blaze unpredictably. That’s just the way it is, historically, perpetually.

Originally published in Dawn, Sunday Magazine, October 23rd, 2016

Comments