Why Lahori musician Asfand is an artist in the ‘truest sense’

“This was very much a process of journaling. The things that I say in my songs are things that I would not allow myself to otherwise say, so it’s a space for me where I can have the jurrat [audacity] that I wouldn’t allow myself otherwise.”

Amidst a deluge of up-and-coming artists chasing trends and attempting to churn out the next commercial hit, Lahore-based artist Asfandyar Ali is a breath of fresh air. His music feels honest, intentional and deeply personal, inviting you to pause and feel.

If you think you haven’t heard his music or seen his art, you’re probably wrong. He’s the genius behind the acoustic version of Maanu and Annural Khalid’s ‘Jhol’, the producer behind Amna Riaz’s recent hit ‘Kya Sach Ho Tum?’ and Maanu’s ‘doob’, the illustrator behind the cover art for Abdul Hannan’s ‘Raabta’, Maanu and Taha G’s ‘Dou Pal’, and so on goes the list of creative output.

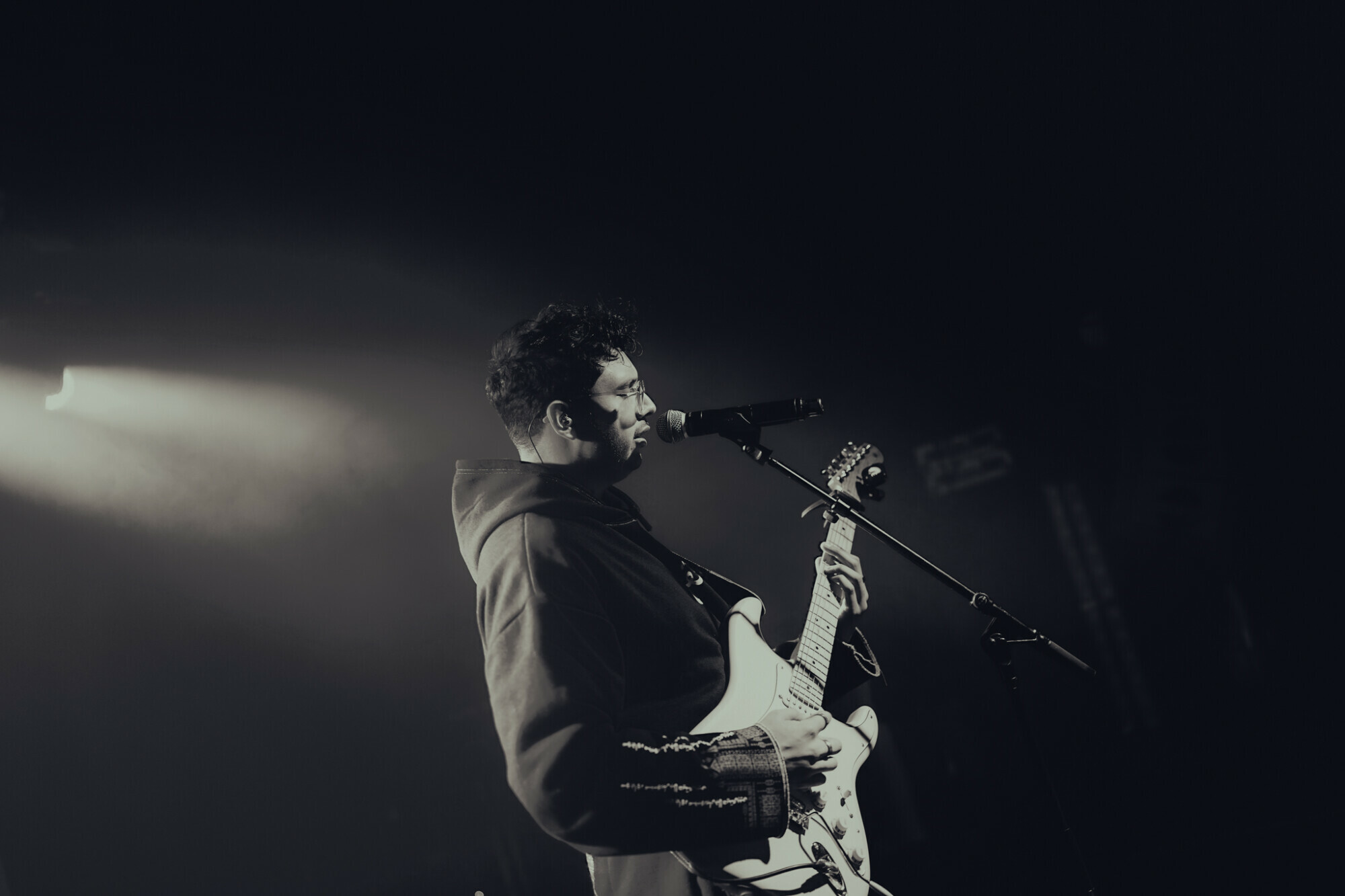

The artist, who goes by Asfand, released his debut album Moss on June 8. While he juggles many hats — he’s a music producer, a singer, a guitarist for the likes of Natasha Noorani, an animator and an illustrator — his album feels like the most honest, stripped down reflection of who he is as an artist and a simultaneous amalgamation of his creative worlds.

I had the opportunity of interviewing him shortly after Moss, spanning 10 songs and a total of 26 heart-wrenching minutes, came out. Naturally, my first question was: why Moss?

“I named it ‘Moss’ because a central theme of this album has been slowing down and healing and it has always been very hand in hand with connecting with nature. When you slow down, things get mossy, it has a negative connotation and positive connotation.”

Asfand went on to explain that the positive connotation “is that you’re slowing down and there’s a paced energy that nature has to it where things take their due time and still end up happening. That is something very refreshing to remind yourself of in this very fast paced day and age.”

Conversely, the negative aspect represented the “stuckness” he experienced. “I was in stasis and stationery for a long time. When you’re numb and stuck doing nothing for such a long time then you might as well have moss grow on you, so it’s in a very healing sense but also in a very rotting sense.”

The name is a fitting metaphor for an album as soul-baring as this is for Asfand. “In contrast to other people who make music, this was not necessarily me making music or making songs to be put out. This was very much a process of journaling. It’s very conversational and it’s very small. The music that I wrote and the songs I wrote are very small because all of the experiences are very personal.

“The concerns and the requests… you know?” he asked, with a laugh.

I did understand. Even an initial listening of the album showed how the songs were highly personal, his lamenting vocals reflecting his state of mind. Although no two songs sounded the same, they all appeared to be part of the same stream of consciousness, creating a coherent listening experience from the start to the finish while highlighting his proficiency as an artist.

In stripping away expectations and industry polish (which isn’t to say the production on the album wasn’t remarkable — it was), Moss insisted on vulnerability in a scene often preoccupied with perfection or virality. There was no artifice here. Each track was filled with emotion that felt lived-in, showing a sort of inner reckoning few artists are willing to put on record, especially for a first album. And in making such a profoundly introspective album, Asfand made the conscious decision to make Moss without any frills, but he clarified that it wasn’t something he “actively reinforced”.

He said his emotional state while creating these songs turned it into a process of journaling, not making music.

“It was always a very emotional process. It was not necessarily a structured process. It was, okay, I’m feeling a certain way, I’m feeling upset, and then I pick up my instrument, and start playing a thing. And then it’s making me feel a certain way. And then I start writing over that. And that’s how it has happened.”

It was evident that this album was his unfiltered diary, but there was a certain universality in the deep sadness Asfand evoked and the emotions he captured. Who hasn’t felt the quiet ache of the lyrics of ‘5AM’: “All alone now once again, look outside it’s 5am.”

By using his music as a space to voice the unsaid Asfand offered listeners not only his truths, but offered them a place to sit with their own. And that is what makes Moss so great: it’s not trying to be for everyone, yet somehow, it finds a way to speak to anyone who’s ever felt a stillness, a sadness.

‘Very necessary’

Elaborating on the process of creating the album, he highlighted that he did not play any more than what was necessary.

“I didn’t really have fun with it, I mean [with] some of the songs I did, but generally it was very necessary. There were not a lot of bells and whistles, it was just this thing was communicating very, very heavy emotion, so that’s why we’ll put it in, nothing else.

“This record was just using all of the essential things that needed to be used to say what I needed to say,” he added.

The bare-bones nature of Moss stands in contrast to how Asfand learned to play guitar, which was through punk rock and heavy metal, the latter being the only genre he listened to for almost “exclusively a decade” — a detail that surprised me given the gentle, atmospheric quality of his music and how warm and funny he was during our conversation, with none of the harsh edges one might associate with a former metalhead.

“Moss is a very raw, and essential and honest expression of emotion. Whatever I wanted is what’s in it and nothing else,” he said, explaining that the track ‘5AM’ was a very good representation of that — a slow and sombre song, with just four chords.

The singer found this funny coming from someone who always wanted to play faster, to play more notes and to play heavier music. But this changed after he worked with other artists. While growing up he was often told to “stop overplaying” and dealt with “a lot of judginess towards metal.”

“So, I guess that developed a bit of an insecurity in me, which made it sad. When I was making my own album, I did not play much. I did not play any more than what was necessary.”

And yet, his early influences did slip through the cracks and became a subtle part of the album. He identified certain guitar riffs that an artist would write only if they had those influences. “It’s interesting because this is another way where influences, whether you like it or not, will seep into or inform your decisions. I didn’t realise this was happening.”

But heavy metal and punk rock aren’t the only genres that influenced Asfand as an artist. He recalled that at 16 or 17, he “actually felt sad and needed something else”.

“And my ears hurt,” he added. “So I started listening to sad music and while I was making the album. I think Phoebe Bridgers was someone who really, really emotionally carried me and that meant it did inform the musical choices I was making.”

Musical inspirations aside, outsider influence and opinions — especially for someone so embedded in the local music scene — can be a double edged sword, leading to a “perversion of the vision” when the point of the album is to express things in the “most raw and honest way possible”.

Asfand was aware of the commercial success backing opinions when people asked him to make songs catchier or faster.

“There could be a tendency to listen to them, but in that process you find that you’ve lost the essence of that song. That is what happened to me in ‘Hold My Hand’ and ‘Letter’. I found that when I was producing the song, after being influenced by certain opinions, I couldn’t understand what the song had become and in three months this happened and then it took me three months to bring it back.”

In a rather meta comment, he added, “if influences are coming into your process, then that is also an experience and that would reflect in your process.” However, while making the album, he actively attempted to evade, in his words “quite literally fight”, others’ opinions, something that held up a mirror to what he was “going through.”

But did he let himself get influenced at the end of the day? “I think that it’s inevitable,” he answered.

Not business

It was evident, throughout our hour-and-a-half-long conversation, where he enthusiastically delved into the crevices of Moss — marked by sentences such as “I will also tell you about that” and “also I would like to mention the visual language of the album” — that commercialisation or mere profit were not at the helm of his creative process. How could they be, when listening to the album felt like one was privy to the singer’s journal?

Asfand explained, as many of us know, that typically, an album is made, one or two singles are released, followed by the entire body of work. For him, it was never about the album rollout.

“It was not from a music business perspective. The function of them being in an album is not the fact that I, as a musician, have put out an album. But it was because emotionally, narratively, these things are all in an album.”

The honesty and precedence of the emotionality was a refreshing change of pace from how Pakistani music, and perhaps music overall, has come to operate, where albums, when they appear at all, are curated more like playlists than cohesive narratives. However, that emotion co-existed with some “harm”.

“It was just a promise that I had made, where I had said to myself that you will do this, you will not put out other music before you have said all this stuff, because I made a promise to myself who was going through these things. That’s why it took that long.”

The release of individual tracks from Moss was not linear or evenly spaced. ‘Shades of Blue’ for example, came out in 2021, ‘Good Side’ in 2022, and ‘Letter’ in 2024. Even the fragmentary releases stayed true to Asfand’s authenticity because “life happens in the middle and lots of life has happened”.

“But I needed to do this. I couldn’t move on until I had finished it.”

Another reason the tracks came out with such long intervals — “You know what? There’s no reason. Sometimes musicians have bad work ethics.” Asfand revealed that initially, the album was supposed to be his thesis project at university, something his thesis advisers discouraged him from because the limited amount of time could translate to less polished music or songs not receiving the recognition they deserved.

“But little did they know they were talking to Asfandyar, king of delaying things. It took another three years after I graduated in 2022. I thought that if I had not listened to them and released it, it would have been great. But now it’s done. It’s fine.”

The rather relatable procrastination (I’m writing this article months after speaking to Asfand) didn’t mean there wasn’t a desire for him to make his album public. “It was on my mind for the longest time [but] I got busy with other projects, and often my own art has been compromised in that process.”

He recalled, in a “light-hearted manner” that he said to himself and a few friends in December 2024: “If ‘Rose Coloured Planet’ does not come out right now, before the end of this year, I will kill myself.”

“And it didn’t.”

After listening to Moss several times, and letting it be the background music and fuel for my own breakdowns, I was glad he didn’t follow through on his promise.

“I didn’t kill myself. But does that not mean that I’m not a man of my word?”

Looking out the window

Without me having to prompt him, Asfand eagerly volunteered to talk about the visual language of the album and more specifically what the cover art for Moss and its previously-released songs represented. A quick scroll down his Spotify page showed that the art had one unassuming, standout theme — windows.

The album’s cover showed part of a translucent window, with overgrown shrubbery surrounding it, a constant theme, he told me, of overgrowth especially of nature in human spaces. “That was a very big thing in my exploration of it all.”

The covers of ‘Shades of Blue’, ‘5AM’, and ‘Good Side’, all part of the album released before Moss was, had a similar theme.

“‘5AM’ is sort of a literal window where you’re literally looking and seeing plants and it’s this dark sort of thing. ‘Shades of Blue’ is also a window but it’s a window in a little more of a like a thematic sense where there are cutouts and you can see into a room but it’s not a literal window and then ‘Good Side’ is also a sort of window in the fact that it’s like you’re looking into a space.”

“This theme of windows and overgrowth and moss is very interesting to me because it’s like you’re looking into a person but at the same time it’s also like you are looking into a space.”

In ‘5AM’, Asfand is literally inviting his listeners to “Look outside, it’s 5am”, reigniting the recurring theme through his lyrics as well.

“I think that window means a few things for me. In one way it’s sort of a window and seeing my space and how my physical space is being taken over by all of this greenery and this shrubbery. On the other hand it’s also a window into my headspace because this bedroom sort of theme can also be seen as my like brain as well.

“Your brain has been in stasis for so long or it’s healing that this moss has started to grow on it. With the final cover art, it’s a window that’s looking into my bedroom and the window is covered on the outside with all of this greenery [which is] a representation of when you leave something for long enough firstly that nature and slowness will reclaim it and secondly it’s communicating that when you leave something alone for long enough, it will heal in that nature will reclaim it. And it’s also when you leave something so numb and unfeeling and untouched for so long, it will rot and nature will reclaim it.”

The idea tied back into the very name of the album, and how the state of being stationary can lead to moss growing on you. The feeling comes through the music as well — with the interlude ‘25.10.20’ and its repeating chords reflecting stillness that feels both comforting and stifling. His music doesn’t rush anywhere, mirroring the way moss gathers slowly, quietly, until you look up one day and see how much has taken root.

He concluded his layered explanation with an off-handed, “but yeah, love windows,” that had me holding in a chuckle at how casually he summed up something he’d spent so much care in both creating and unpacking.

While the art for Moss set the scene visually, the album also spoke in a different kind of language: one with no words at all. Through four instrumental songs — an intro, an outro and two interludes — the music holds the story on its own, allowing textures and chords to carry what lyrics might have been unable to. The album’s first track, ‘Moss // Intro’, a gentle instrumental that softly fades in, prepares you for the emotional journey ahead with calmly repeating guitar chords and soft bells.

“Language is obviously such a huge and essential way of communication, but when you prescribe a language to a person or a conversation, although it means you can express yourself in a world of ways, it also means that you are not limited to expressing yourself within the realm of that language,” he explained.

“With these instrumentals, there are certain feelings portrayed that you don’t really need words to ground into anything. Two of these songs are literally that, they are songs that are just feeling, they are not really even songs, one of them is literally just two chords played over and over again. But there is a feeling that, when you really listen to it, is being portrayed.”

The rather conscious sound choices throughout the album, not just in the instrumentals, added not just authenticity but a layered listening experience. In ‘Letter’, for example, one can hear pages turning in the background of the song, painting a more striking picture than just words being used to describe the feeling of reading a letter, instead you’re there with him as the pages turn.

In ‘Moss // Outro’, tolling bells return in what feels like a full circle moment from the intro, but the now-lamenting sound morphs into glitchy sound effects, partially accompanied by a soft guitar strumming, creating a sense of uncertainty and discomfort as the album draws to a close.

“The way that sounds is glitching, to me sounds like a person’s voice starts breaking while they’re screaming and that’s such a guttural and very visceral feeling. I found it to be very liminal and offputting,” he said.

At the same time, Asfand found it to be bittersweet because the haunting sound had an element of prettiness to it. “I think that’s kind of the way that it is okay, jo hua so hua [whatever happened, happened] and now the album is over.”

Creative identities

What started with him just wanting to play the guitar, something he “really enjoyed”, snowballed into numerous creative pursuits.

“Bold of you to assume I am successful at holding these creative identities,” he said when I asked how he handled his myriad of creative identities after he explained the meticulous intentionality that went into designing art for music, not just his own but that of other artists as well. From muted colour to where a phone was placed in the frame for the cover art for Abdul Hannan’s ‘Raabta’, Asfand detailed how with the presence of intention, the meaning of songs could be better communicated.

However, the musician didn’t just stop at producing, playing guitar, singing and creating visuals, he sometimes directed his own music videos and wrote his lyrics — in addition to his other animation work.

“I think it’s really, really nice to also be able to wear these different hats. Because it means that I get to be involved in so many different processes. I can make sure that everything about my music at least is being represented in just the most way that it can be, I get to inject meaning into all folds of the package.”

Yet, he was aware of a “thing of control” and that he found it difficult to give the reins to someone else or let go of creative control of his projects. “Which I feel is something that I could learn to get over a little bit, because when there are other creative minds and people working on things together, then a new thing is made in that convergence. And that’s really exciting.”

Take for example, ‘Shades of Blue’, Asfand produced the music, recorded the lyrics, mixed and mastered the song, directed, edited, colour graded and starred in the music video, created its VFX, and did the marketing. “The songs are going to end up being a little delayed. In that sense, it’d definitely be good to have a team to help you do these things, which is why I now try to involve people who I like working with or who I’ve worked with in the past.”

What’s next

After he evidently poured his heart and soul into Moss, I couldn’t help but ask Asfand what was next for him.

“Now that the album is out, I feel a few steps into being an artist for the first time again, which is exciting. It would be nice to just be in a position where I have my fun with it, and that I connect to people and an audience.

“That has been my dream since childhood to just be on stage, be playing to people who like hearing what I am playing.”

As he wraps up opening for Maanu on his 4UK tour, Asfand may be slowly and steadily progressing towards achieving his childhood dream. One thing is for certain, if you take the time out to listen to one recent Pakistani album, let it be Moss (especially if you’re going through emotional turmoil).

During our chat, often interrupted by shaky internet connections, I could hear gentle guitar strumming in the background, almost as if his instrument was an extension of him. In a later voice note he told me that it made him feel more comfortable with himself and that he liked “noodling” while talking to people. It reminded me of what Asfand’s brother and fellow musician Sherry, once said to me, “In the truest sense, Asfand is an artist” — and after listening to his music, I couldn’t agree more.

Comments