There is a lobby system for casting in the Pakistani entertainment industry, says director Jasim Abbas

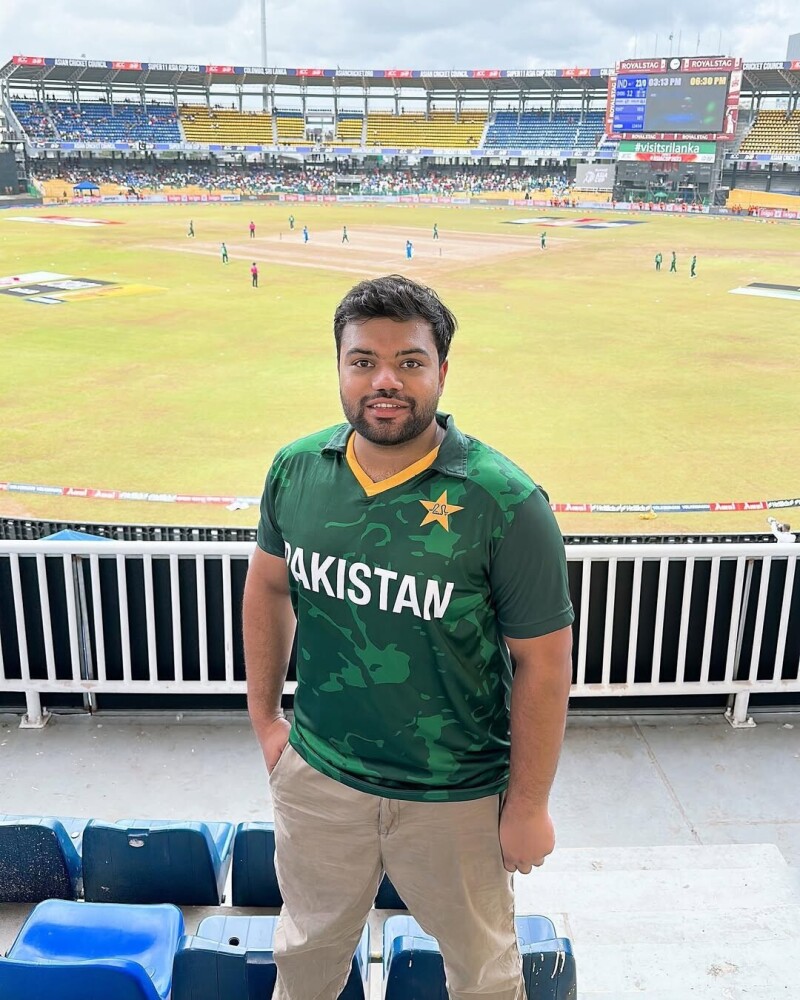

Twenty-nine-year-old Jasim Abbas, now an established Pakistani director, believes he is still struggling to make his mark in the entertainment industry. The incessant, unethical practice of nepotism often gets people with strong connections a foot in the door, but for Jasim, the struggle was real, and it still is. After spending his childhood and young adulthood in the United Kingdom, Jasim decided to return to Pakistan to bring his creativity to life through storytelling, but all he ever experienced was rejection — lots of it.

“The fact [is] that in Pakistan, be it an actor, a producer or a director, if you are trying to come up with new ideas, if you are trying to bring some change, the only thing you will face is rejection,” Abbas told Images.

Luckily, hard work and consistency got him a few decent projects. He went on to direct popular dramas such as Yeh Ishq Samajh Na Aaye starring Zarnish Khan, Mikaal Zulfiqar and Shehroz Sabwari, and Dil E Benaam for Aur Life TV. He recently wrapped a new drama Rafta Rafta and has three projects in the pipeline for Green Entertainment, Express Entertainment and A-Plus.

The toughest part, according to Abbas, was to land his first major break as a director. “Nobody is going to give you your big break,” he said. He partly attributes this shortcoming to channel heads not acknowledging credentials and qualifications, even if it is a master’s degree in filmmaking, which Abbas earned in 2018 from the University of Westminster, London.

“In Pakistan, nobody cares what you have done. Nobody! The only thing they [TV channels] would ask is who you are related to, and where you are from. For a new actor, producer, director, or anybody in show business for that matter, it is so damn hard to earn your place.”

Nepotism is a deep-rooted issue, particularly in Pakistan’s entertainment industry and actors with strong connections justify it by claiming that nepotism is rampant in other fields as well. Although that argument holds merit, Pakistan’s entertainment industry in particular is full of established actors, such as Rubina Ashraf, Javed Sheikh, Bushra Ansari, Asif Raza Mir, Saba Hameed, Naumaan Ijaz and Zeba Bakhtiar, among others, who have their children on the forefront of television projects. Even Humayun Saeed’s younger brother is part of the acting industry. Nepotism leaves very little room for emerging talent to shine and get ahead in a cutthroat entertainment business.

“If you have relatives or if you are related to any Khans in the industry, you are going to get your break just like that! If your brother, your sister or uncle are acting already, that is the best way for you to get into the industry,” Jasim shared.

The 29-year-old director revealed that casting for projects often takes place at high-end parties that comprise of big names in the industry. “There is a lobby system for casting,” he revealed.

He believes that regardless of talent, actors are cast in projects because they are backed by powerful names. “There is a monopoly of three to four big production houses that just want to work with select actors. No matter who they are casting, they just don’t care,” he claimed.

“It is easier for such individuals to land lead roles because they are sons and daughters of powerful celebrities. Can’t you see what is happening at GEO Entertainment, ARY Digital and HUM TV? It is the same lobby system. The disadvantage is for people like us who have struggled and are easily overshadowed by these people,” he said.

He shared that if you try to talk about nepotism openly, people in the industry will shut you down. “The father is in the industry for the past 50 years and is preparing his son or daughter to be part of the industry.”

According to Abbas, channel heads observe celebrities’ Instagram followers, their engagement on social media and accordingly make calculated decisions to cast them in key roles. These actors are categorised as A, B and C-grade actors. Characters are allocated based on these categories, according to him. “If you argue that a role is not suitable for the actor, the channel heads would say, ‘You will tell us? We have to look at our market value.’ You just stand there, quiet,” he said.

“You have to sacrifice your creativity because of them.” The director also revealed that after filming a pilot episode, channel heads would review and provide feedback. “They will call and say, why have you given the new actor one minute of screen time? Nobody wants to see new talent. Everybody wants to see the big stars on-screen,” he said.

“Even if you try to pitch newer artists to channel heads, they will respond by saying that they have no market value.” If channels refuse to give newer faces a chance, how will they grow as artists, Abbas questioned. Certain channels also reserve good roles for established actors that put newer artists on the sidelines, he believes.

Abbas recalls the difficulty of arranging meetings with channel officials, or even getting a hold of them. Once he did, he would discuss his novel ideas and although they would appreciate his thought process, they would tell him that no senior actor would want to work with a novice like him.

Many Pakistani actors completely negate the quality and demands of scripts because they want to work with more established directors. “We’re not looking for degrees, we’re not looking for vision. What we’re looking for is a bigger name,” Abbas says the channel officials would tell him. Because of this downside, young newbie directors like Abbas experience serious rejection, despite their creative ideas for TV projects.

“We really want a bigger name as the writer, we need bigger names as cast members, and we need a bigger name as the director. If you are going to direct it, who is going to join the cast?” Abbas quoted officials as saying.

He also claimed that well-known actors would only work with a new director for the sake for money, not creativity. These actors would hike their salaries and instead of charging Rs3 million, they charge double the amount, he said, relating an instance of when an A-list celebrity once told him that he is solely working on his project for the money.

The Islamabad-based director revealed insights about another pressing issue facing Pakistan’s entertainment industry — the casting couch. Silence over action may be causing this practice to spread like an infestation. “I have seen big names in the industry asking for so called ‘favours’ from actors in return for bigger roles,” Abbas commented.

In a showbiz industry like Pakistan’s, it is important to socialise and network at events and parties. Abbas not socialising with these people put him at a greater disadvantage as a novice director. “I was told by a lot of friends in the industry that I was not going to get good work from channel heads if I didn’t party, smoke or drink with them,” he said.

Because Abbas was fairly new to the industry at the time, he decided to attend a party to see how things went. “We can do this favour for each other,” Abbas related the words of an unnamed woman who approached him at a party. “I am going to get you in touch with somebody who will get you great work at a channel, but in return, you need to get me the main lead or second lead role in your project,” she had said.

Many young actors were also present at the party and approached filmmakers, directors and producers for work. Abbas said they openly received invitations to spend a night with them in exchange for roles. “That one party changed my life, and the way I thought,” Abbas said. “I said fine, I am just not going to go up to people and ask them for work.”

Abbas was committed to his work ethic and personal beliefs that helped him steadily grow in the industry. He worked on international advertisements and short films that received praise, and with some luck, he received a call from Pakistan to work on a project, his debut drama, Ahl e Wafa. Recently, Abbas has worked with numerous artists who anticipate change in the industry and understand the craft for what it is. However, he never heard back from bigger channels because they were looking for bigger names. “If you don’t have an A star writer with you, they [the channels] will not even talk to you.”

Pakistan’s drama industry is trailing behind for this very reason. Established writers call the shots and their stories end up becoming television “gold.” These scripts, penned by ace writers, are recycled, monotonous stories that Pakistan’s TV industry is wrestling to outgrow.

According to Abbas, channel heads are still stuck at a point where they argue over who will receive the most limelight on a drama poster.

“Actresses with fairer complexions get lead roles, while artists with darker skin tones get the second lead. Channels want to see brighter faces. When are we going to get out of these complexes?” he asked.

While working abroad, Abbas felt that an actor is treated as an actor. “In Pakistan, if the call time is 11am, an A-list actor would arrive at 3pm. If we complain, the channel heads would say ‘it’s okay, just accommodate them’. No professionalism, no nothing. Why, though?”

Pakistan’s entertainment industry will remain at a standstill unless these deep-seated practices are brought to a permanent halt, which is unlikely. However, with emerging channels and newer teams, Abbas is hopeful that things may change for the better.