The room is lined with books — heavy duty tomes in Urdu nudging shoulders with historic odysseys in English, the works of Iqbal and Faraz on one wall, Shakespeare and William Dalrymple on the other. Another wall is lined with a selection of paintings, freshly framed, evidently new to this room. There are black-and-white photographs in frames and on the walls and, when I scrutinise them up-close, their subjects are some of the country’s most renowned faces. A thick sheaf of papers lies on one chair.

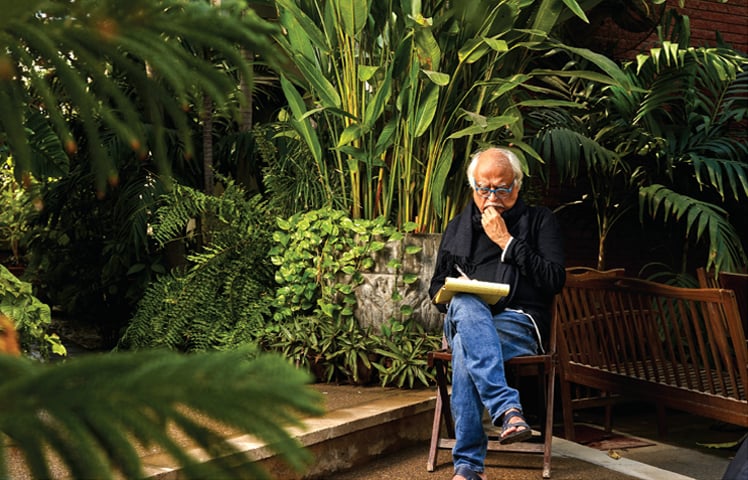

It is because of this particular sheaf of papers that I’m meeting the legendary Anwar Maqsood, who turned 81 last September.

He is one of Pakistan’s most loved, most iconic playwrights and the thick pile of notes encompass the latest script that he has written for theatre, a production titled Saarhay Chauda Agust. He is currently in the process of tweaking it and, knowing Maqsood’s penchant for perfection, it is likely that he will continue to do so till May this year, when the play is scheduled to be staged.

Maqsood had once focused his creative energies entirely on TV and a large chunk of Pakistani television’s classics can be credited to him; gems such as Fifty Fifty, Silver Jubilee, Studio Dhai, Studio Pawnay Teen, Aangan Terrha, Half Plate and Loose Talk among them.

Anwar Maqsood is one of Pakistan’s most loved, most iconic playwrights and wits and a script by him tends to be in a league of its own. He is returning to theatre in May with the third and final play of his ‘patriotic’ Chauda Agust trilogy, in which Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Mahatma Gandhi face-off in a court of law

In 2011, though, he turned his attention towards theatre, on the insistence of a young group of thespians called Kopykats Productions. Their first collaboration together had been a patriotic narrative called Pawnay Chauda Agust [A Quarter to 14th August]. Laced with the witticisms, sarcasm and emotion that was quintessential Maqsood, the play had been a huge hit.

Many other theatrical productions followed, including a sequel to the first one, titled Sawa Chauda Agust [A Quarter After 14th August]. More than a decade later, he has written the final part of the trilogy, which has now progressed to a ‘saarhay chauda’ [fourteen and a half].

What about Chauda Agust [14th August] itself, the date on which Pakistan gained its independence? “I won’t be writing that,” he says solemnly, “because to my mind, Pakistan hasn’t yet seen a Chauda Agust worth celebrating. Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah created Pakistan with such hard work and high hopes, but nothing has come of it.”

Maqsood says this solemnly, his eyes sad and I’m reminded of the past many times when I have watched his interviews on TV where he has spoken just as desolately about Pakistan’s ruin. His language has always been precise, his observations true, and anyone with even an ounce of patriotism is likely to feel sorrowful when hearing him speak.

His theatrical plays have the same power. It’s now commonly accepted that one should carry a thick wad of tissues when going to watch a play penned by Anwar Maqsood. There’s plenty of humour but there also tends to be a deep underlying sadness that surfaces in certain scenes. Is this new drama also going to follow similar lines? “There are light moments but the story this time has some very serious nuances,” he says.

He proceeds to narrate the story to me. The earlier two parts featured a range of historic personalities together: Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Gen Ziaul Haq, Allama Iqbal, Maulana Shaukat Ali and Jinnah, among them. The finale will be pitting Jinnah against Mahatma Gandhi.

“A court case has been filed, questioning who is to be blamed for the formation of Pakistan,” elaborates Maqsood. “The argument is that had Pakistan not been formed, India would have had been extensive and would be flourishing. Jinnah and Gandhi are called to court and in the quest to find out the culprit, they visit four different areas: Kashmir, Lahore, Delhi and London.”

Their first stop is Kashmir, where the two pass the Line of Control [LoC] and enter an apple garden where there are no apples. The trees are wilting away.

“Jinnah meets a young boy who greets him with a salaam. ‘Jeetay raho [Live long]’, he replies. The boy replies, ‘Mujhay dekhein. Main gyara ya baara ka ho gaya hoon. Kashmir mein bachay ko koi aur dua de dein, koi aisi dua dein jo puri ho jaye [Look at me. I’m 11 or 12 already. Bless a kid in Kashmir with some other prayer — one that could possibly be fulfilled]’.”

Maqsood’s eyes well with tears as he recounts more of Jinnah and Gandhi’s experiences in Kashmir. He speaks softly, pausing at just the right time and I find myself crying too. That’s the power of Maqsood’s pen. Have you cried every time you have read out this part of the script to someone? “Yes, every time. My heart is pained by everything happening around me. You will cry,” he asserts.

He changes tack to more humorous scenes. The trip to Lahore offers plenty of hilarity — I won’t mention the jokes here because they would just end up being spoilers. It is undeniable, though, that the upcoming play is going to be a powerful one, the sort that needs to be shown to full houses, day after day.

It was for this reason that Saarhay Chauda Agust got delayed several times. Both Maqsood and Dawar Mehmood, CEO of Kopykats Productions, wanted to stage the play to a packed hall rather than to an auditorium operating at half its capacity because of the pandemic.

“This is the last one,” he muses. Your last play? Would you ever really want to ever stop writing? Maqsood rephrases. “The last one in this series. I may write again after this but it won’t be for this series. I have been writing for 60 years now, and I just want this play to go well.”

He continues, “I love and respect the Quaid-i-Azam with all my heart and it saddens me that today’s youth don’t even know who he is, the sacrifices that he made.”

His work has always inspired patriotic love within his audience and yet, given Pakistan’s perpetual troubles, does he sometimes feel that his efforts have been in vain, that there is no point in propagating nationalism in a country mired with so many problems?

“No, I don’t think so,” he says. “I have always written what I have felt strongly about. I could have worked anywhere in the world, but I chose to never leave Karachi. Jaisa bhi hai, hum burray nahin hain magar badqismat zaroor hain, humein kabhi achha aadmi nahin mila [Whatever it may be, we’re not bad but we have certainly been unlucky, because we have never been able to find a good leader]. All over the world, a new day dawns and it’s full of hope. In Pakistan, every new day is worse than the last one.”

Earlier, there were rumours that he was working on a script for a movie with Shehzad Roy. It had also been heard that he would be working on a theatrical script in collaboration with Sania Saeed. What became of those projects?

“My scripts require time and effort, and most people just don’t have that kind of time anymore. They are in this rush to earn money, to flit from one project to the other. It’s endless,” he laments.

Does he sometimes miss the days of yore when the recording of a single scene was preceded by hours of rehearsals? “We would rehearse for five days before shooting scenes for Sitara aur Mehrunnissa,” he reminisces about the making of the romance that he had penned, starring Atiqa Odho, Sania Saeed and Sajid Hassan.

“It took us four or five months to record the whole drama. For Half Plate, we rehearsed to the extent that Khalida Riyasat knew every line by heart. And now, suddenly, everyone has been wiped away, everyone is gone.”

Remembering the late Moin Akhtar, with whom he worked extensively, he says, “Sometimes, when I write a good script, I lament that agar Moin hota toh yeh achha karta [had Moin been around, he would have been able to do justice to it]. No one has been able to take his place.”

I observe that similarly, no one can write a script the way he does. Did he ever have qualms, perhaps early in his career, that his latest work should be able to match his past successes?

“Writing always just came naturally to me,” he answers. “For six years in school, I studied with Khawaja Moinuddin, who has authored scripts such as Taleem-i-Balighan and Mirza Ghalib Bunder Road Par. He used to tell me that what I wrote would always be very different. I would write an essay on Mirza Ghalib and he would find himself laughing. Likhtay raho [keep writing], he would tell me. And so I did.”

This doesn’t quite answer the question that I had asked him but I conclude that perhaps he has always had such an innate genius for writing that he has never been assailed by self-doubt.

Did he ever get arrogant when each successive project would be a success? “No, not arrogant, but I think I sometimes become like a child, worrying over every little detail. I don’t want anything to go wrong in my script.”

And did he ever, in a career that has always been stellar and ahead of its time, feel an ounce of pride when people would stare up at him, riveted by every word he spoke? “I’m more concerned that they should understand what I’m saying,” he smirks. “I look at who I’m addressing and I change the way I’m talking accordingly.”

We return to the topic of Saarhay Chauda Agust. Kopykats Productions tends to show their plays in cities across Pakistan as well as in key locations around the world. With Gandhi taking centre-stage in this latest offering, has he had to tweak the script in order to make it politically correct and not offend the sentiments of the Indians in the audience once the play is shown internationally?

“It’s all in good humour. I don’t think that they will get offended,” he says.

Even though there may be certain quips that lean towards being politically incorrect, it’s a known fact that Maqsood dislikes it when anyone tampers with his script. “Meray alfaaz buss koi na badlay [No one should change the words that I have written],” he has often said. It’s a grievance that has led him to sometimes walk out of projects.

A script by Anwar Maqsood, after all, tends to be in a league of its own, knitted together with the humour and poignant sadness that define his work, leading to halls packed with audiences, standing ovations, laughter and plenty of tears.

Saarhay Chauda Agust is going to be 90 minutes long and theatre in Pakistan, after suffering for two odd years because of the pandemic, is likely to revive with full gusto. That’s the magic of Anwar Maqsood’s pen.

Originally published in Dawn, ICON, February 20, 2022

Comments