What should Pakistani cinema's New Year's resolution be? To play nice with each other for once

After two years of uncertainty and gloom, cinemas officially came alive on December 17, 2021, when its saviour — a young, radioactive spider-bitten superhero and his two alternate world avatars — threw their web-lines straight into people’s wallets.

Who says Spider-Man doesn’t rob people? No Way Home emptied pockets faster than Pakistan’s down-spiralling economy.

No Way Home’s box-office (unaccountable at this time) is greater than great. But it comes with a cost: the resurrection of bad business practices for the local industry.

No Way Home is a calculatingly manufactured fluke; it was destined to break records worldwide. In Pakistan, a domestic film’s simultaneous release with No Way Home would have been an excellent opportunity to cash in big bucks at the box-office. The practice entails capturing the overflow of a popular film’s audience — those who could not get tickets or would not wait for the next show — to watch another film instead.

The year 2022 has, perhaps, the strongest line-up of commercial Pakistani film releases since Pakistani cinema’s rebound 10 years ago. But film producers, distributors and cinema owners need to make a new year’s resolution: to play fair with each other

In theory, it’s a great, time-worn strategy in the movie business. At least that is what first-time producer Kamran Bari deduced.

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

Kahay Dil Jidhar (KDJ), released by Mandviwalla Entertainment, didn’t even get a chance. The shows it got were paltry, scheduled at inconvenient times. Even in its second week, as per our data, the shows were scheduled between morning and evening, and not nights, when typically, Pakistani films have better turnout.

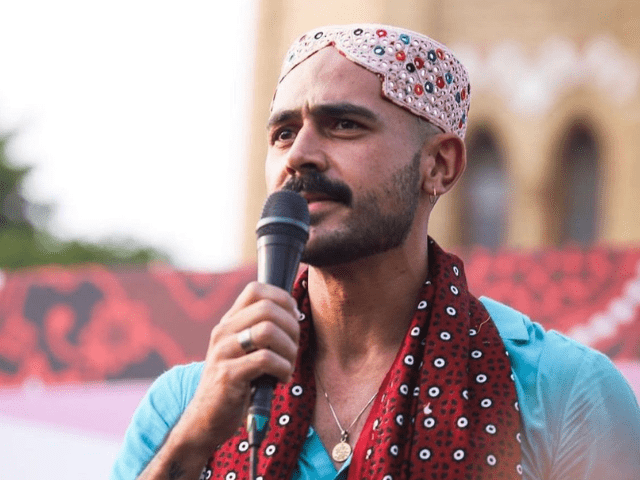

This malpractice was universal across the country. The argument from cinema owners was that the audience wasn’t interested in the Junaid Khan and Mansha Pasha starrer. In reality, No Way Home was given almost every available slot and screen there is.

Historically, far worse films have done better at the box-office.

So the question becomes: can a Pakistani film make money when it has far fewer shows in cinemas?

No, it can’t.

Filmmakers and distributors certainly seemed to create a lot of hoopla once upon a time, calling out Bollywood releases for confiscating screens and not giving Pakistani films a chance. How is this any different?

Is the cinema business that scared from the non-performance of high-profile films such as No Time to Die, Dune and The Eternals, that they thought to not take any chances at all with local films? Isn’t this a bad sign for local producers, who can very well get swindled without prior notice when it solely becomes a matter of business for cinemas?

Can multiplexes not allot one screen exclusively for a Pakistani movie for two weeks, especially when the rest of its screens are jam-packed by a vastly successful foreign movies’ crowd (in this case: carryover films had already been in cinemas a week before No Way Home’s release).

The practice may only get messier as the year rolls by, if KDJ’s case is any indication.

The war between filmmakers, distributors and exhibitors — ie. cinema owners — is a tired old one; it’s so dated that Icon has exhausted its ink writing about it. Yet, it persists.

While nothing can be done about KDJ, provided they see the folly of their ways, the “industry” — film producers, distributors and cinema owners — can, at the very least, make a new year’s resolution.

It doesn’t have to be fancy, bombastic or longwinded. It can be as simple as a proclamation to play fair with their fellow brethren.

For producers, the resolution could be to refine their films in the edit while they have the chance (since they’ve already shot their movies, it’s no use telling them to revisit the screenplay). Secondly, they should not pressure distributors to release the film without a workable, mutually consented strategy.

For the distributors, the resolution would be to release films in a staggered manner (ie. one after the other), so that Pakistani films get year-wide visibility and are not clumped together during Eid seasons where they eat away another Pakistani film’s potential business.

Is the cinema business that scared from the non-performance of high-profile films such as No Time to Die, Dune and The Eternals, that they thought to not take any chances at all with local films? Isn’t this a bad sign for local producers, who can very well get swindled without prior notice when it solely becomes a matter of business for cinemas?

For the exhibitors, the resolution would be to not give into peer pressure and relationships (which happens a lot), allot a fitting quota of screens to Pakistani films, and pay distributors their share of the dues on time (the issue of lingering payments from before the Covid-19 days has yet to be resolved by some cinema owners).

After all, the industry needs all the help it can get. Let’s make a resolution to play nice with each other for once, shall we?

There is a reason why Icon is suggesting such a pledge this year. With a string of high-profile releases set to debut in 2022, the year is going to be a doozy.

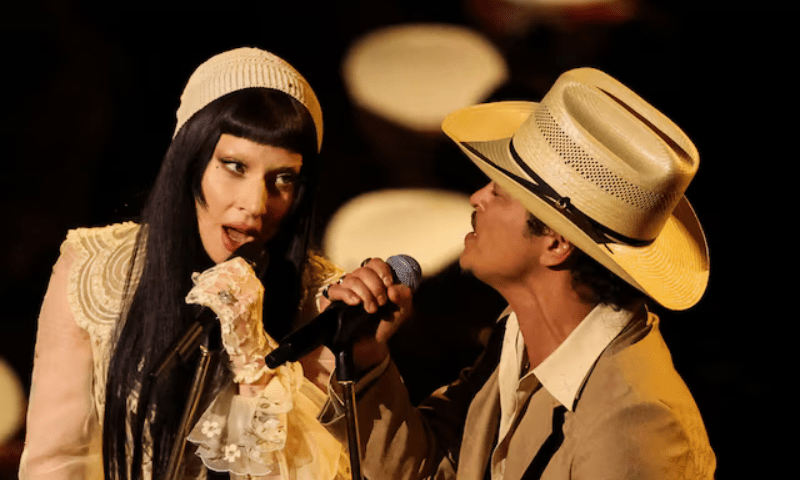

Consider the films waiting to be released this year: The Legend of Maula Jatt, Quaid-i-Azam Zindabad (QAZ), London Nahin Jaunga (LNJ), Ghabrana Nahin Hai (GNH), Ishrat Made in China, Chakkar, Zarrar, Tich Button, Dum Mastam, Money Back Guarantee (MBG), Neelofer, Parde Mein Rehne Do, Qulfee, Umro Ayyar, Allahyar and the 100 Flowers of God, Shoaib Mansoor’s mysteriously titled ABG, Javed Iqbal: The Untold Story of a Serial Killer, Once Upon a Time in Karachi, Pakistan’s first Balochi language film Doda (it will be dubbed in Urdu, according to the producer), Peechay Tou Daikho, Yaara Vey, and the Ahsan Khan-Ayesha Omer-starrer Rehbara among them.

I’m sure there are many other independent Urdu language productions that I’m forgetting about, waiting for the right moment to spring their trailers on to unsuspecting audiences. The year 2022 has, perhaps, the strongest line-up of commercial releases since Pakistani cinema rebounded nearly 10 years ago.

This could be the real revival of movies, if the powers that be don’t bungle it up.

As per our information, the industry is still at a deadlock when it comes to agreeing on a sensible release strategy. Knowing full well about the other’s schedule, no distributor is sitting down on a table to talk these things through. Eid is still the most coveted time of release for all, as per our information.

A good number of titles mentioned above — GNH, QAZ, MBG, Dum Mastam — are eyeing Eidul Fitr (GNH and Dum Mastam have already announced their release dates). Tich Button’s release on Eidul Fitr is also a big possibility, since the only alternate “big” release date — Eidul Azha — will likely see the release of The Legend of Maula Jatt and the Humayun Saeed-starrer juggernaut, LNJ.

ARY Films, which distributes both Tich Button and LNJ, will never release two of its titles on the same day.

The Yasir Nawaz-directed Chakkar, according to sources, will likely come out between the two Eids, like Teefa in Trouble, which made over 330 million rupees in Pakistan in 2018. It’s a surprise why others aren’t being as sensible as producer Nida Yasir, because this is as good a date as any for release.

Back in 2018-2019, even three titles seemed too much for audience consumption because they impacted the overall box-office earnings during the holiday weekend. Four titles, if not more, are detrimental for one holiday weekend, especially since Pakistan has a limited number of cinema screens in operation, and there is little to no information about how many more cinema screens might be functioning at that time (there is little data as of now, but some screens have shut down while others are negotiating outstanding rent issues with their landowners). There is some hubbub about new screens opening soon, but that remains a rumour for now.

Since almost all of these titles are, professedly, big releases that have guaranteed box-office earnings, it makes sense to consider other holidays for release. For example: since 2013, only one film — the Nasir Khan-directed, Muhib Mirza and Sanam Saeed-starrer Bachaana — cashed in on the Valentine’s Day weekend.

Conventional holidays such as August 14 (a great date for QAZ or Shaan Shahid’s patriotically inclined actioner Zarrar), lands right in the middle of Muharram, so that’s a no-go.

The holy month of Ramazan — when Pakistani film business grinds to a halt — takes place throughout May, which is usually a great time for Hollywood movies. June and July become the only other viable release times because of the summer holidays, and the bookending Eid vacations, but the industry can only fit so much in during that short window.

Clearly and surely there is much to debate by the movers and shakers of the industry in the coming months.

As any layman can deduce, the industry needs to sort out its grievances more than ever in 2022, otherwise, we very well could end up repeating the mistakes of our past.

With the start of what could be a very prosperous new year, let’s resolve to not stoop down to dirty shenanigans and monopolies. Let’s be accommodating and serviceable for a higher cause, for once.

Originally published in Dawn, ICON, January 9, 2022

Comments