Karachi's recording studios have drowned in rainwater. Where does the music community go from here?

“It’s rained before but I’ve never seen a flood like this in my life,” says Natasha Baig. The singer-songwriter and producer was filled with dread as she watched the water gather below.

“I live in a flat on the fifth floor. Despite that I was so terrified because I could see it flooding the ground below. I thought the water would reach my floor. The main gate of our apartment was completely blocked by floodwater.

“But there was no point in leaving to get to the studio,” she adds quietly. “We couldn’t have done anything.”

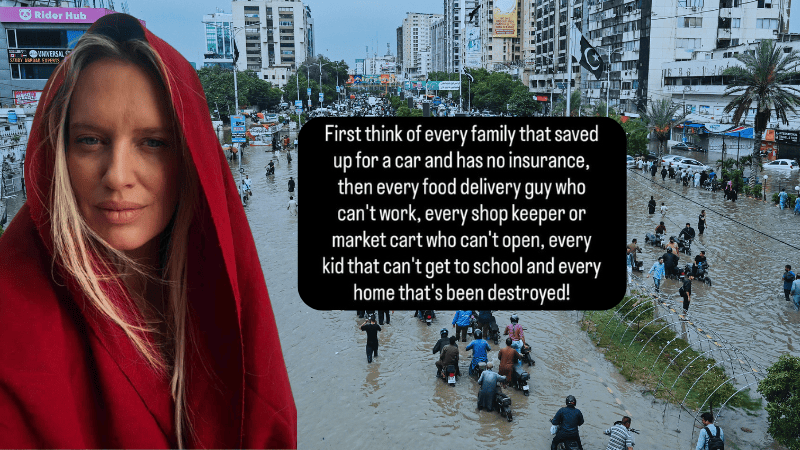

While different parts of the country have experienced unprecedented rainfall recently, resulting in both urban and rural flooding and displacing several hundreds, in Karachi, on August 30th, it rained a recorded 345mm in one day, shattering a 90-year-record.

Photos and videos of the city resembled scenes right out of an end-of-times disaster film. Peoples’ homes were inundated with water and they were forced to find higher ground on the upper floors or the roof until they could be evacuated. Underpasses were filled with water and boats had to be sent to rescue people stranded on the streets.

In Clifton, Neher-e-Khayyam overflowed and, with standing water on the streets reaching four to four and a half feet deep. You couldn’t tell what was land and what the stream. No one was prepared for this.

Least of all, Karachi’s already struggling musician community. Most of them had their studios, in which they had invested everything they had, in basements.

While music has always been a part of Pakistan’s cultural identity, most artists have always struggled to make ends meet consistently. With regular socio-political upheaval sometimes deeming the arts ‘haram’, the threat of terrorism making public events such as concerts difficult to safeguard, economic recessions and, most recently, the pandemic limiting freedom of movement, art has always struggled to survive in Pakistan.

When disaster struck

Then the rains hit their studios and drowned it all. Natasha’s studio at Saba Avenue, DHA, which she co-owns with her manager Hasan Effendi, was one of the worst affected. Photos she posted online showed water nearly up to the roof. Tables, sofas, keyboards floating on dark, murky waters. The studio they had spent all of their savings building was gone.

“There is a rectangular window at the top of the one of the walls,” Natasha relates. “The floodwater didn’t shatter the glass, it basically dismantled the whole frame and it fell through. Then floodwater filled the studio to the ceiling like a water tank. Hasan was already on the road and when it started raining like this, he ran towards the office. He told me that when he opened the door more water just flooded in. He shut the door immediately.”

“It was like we were in between the sea,” she whispered.

What was in the studio? “Everything,” she says. “More than half my equipment was there. There were two work stations where songs were being recorded. There were guitars, sound cards, midi keyboard, monitors etc. There was a jam room with drum kits, mixer, sensitive recording dynamic microphones etc. One of our musicians, Zulfi bhai’s new keyboard. All of the recording and performing instruments were there and they’re completely destroyed now. It’s all finished.”

For Ahmed Zawer, one of the bandmembers of the rock outfit E-Sharp, a disaster of this scale was predictable. His creative space, which he co-owns with several partners, Funkaarpur Studio, was also badly inundated by urban flooding.

Why was it predictable? “Because we’ve been here for two years in a ‘posh’ locality like Defence Housing Authority’s Phase 6, right behind main Shahbaz Commercial, and the civic amenities are bad,” he responds almost matter-of-factly.

“All these restaurants that you go to, all of them throw their waste in the backstreet. No one picks that trash up. In these two years, I had tried everything — the Citizen Portal app, CBC, DHA etc but it was of no use. That problem was never fixed.”

This was particularly frustrating for him because his studio was right next to an empty plot where this garbage would accumulate. It contributed in the worst way possible to the flooding of his studio.

The streets outside the studio were so badly inundated with water, they had to wait a few days until they could finally visit the space and assess the damage. The water came up to their ankles. “In a music studio, there is a lot of wiring on the ground,” says Ahmed. “That had really gotten damaged because the water came in from the vacant plot and stood there for two days. It was a disaster.”

Rocky road to recovery

His first tried reaching out to the authorities. He went to the DHA office but was told that the staff was on Ashura holiday. “It was very disappointing because this was an extraordinary circumstance,” he says. “They should’ve stayed to help people out.”

“We then went to the CBC office on Khayaban-e-Rahat but getting there was hard since there was five to six feet of water on the street outside. And we were going to them to help us with our floodwater. The irony was not lost on me,” he chuckles.

He realised, much like the others, that they were on their own. “We got lots of buckets and all of our friends over there,” he says. “The worst part was that it’s not just rainwater, it was mixed with all the filth from the lot adjacent to our studio. We spent eight to 10 hours taking that water out. It was the most traumatic experience I’ve ever had. We took our shirts off because it felt like we’re clearing out the gutter.”

For Kashan Admani, the studio he’d set up in DHA’s Nishat Commercial area some three odd years ago had been a dream in the works for many years. “There was no other facility like this in Pakistan,” he says about Dream Station Productions from his makeshift studio in a house in Zamzama.

“The architect who designed the studio, John Brandt, is one of the best studio designers out there. He’s done award-winning work in Europe and what not. The acoustics were perfect. If there is a band jamming in one room, you can’t hear it outside.”

That’s true. And that studio has also seen its fair share of both local and international talent. After Aamir Zaki passed away, artists collaborated on a tribute song for him in that studio. The BBC Asian Network recorded their series featuring Pakistani artists there as well. Even when Junoon decided to get back together again, they rehearsed in that studio. And finally, legendary drummer Simon Phillips also worked with Kashan in the same studio during a visit to Pakistan.

But by the time Kashan made it through to Dream Station Productions a few days after the rains, it was under three feet of water. He tried going to the studio immediately after the rains but the water on the streets of Khayaban-e-Nishat was so deep that they couldn’t go through even on a 4x4.

How bad was the damage? “It was pretty bad,” he says. “I lost quite a few of my guitars. They were very dear to me and are irreplaceable. We lost quite a lot of equipment. Luckily, we saved our data, the main monitoring system and some of our more expensive gear.”

He sounds oddly optimistic. Not in the hope-is-the-only-recourse kind of way that the others’ I spoke to adopted. Why? I ask somewhat suspiciously. “The financial loss isn’t that much because luckily we were insured.”

Even if he’s not compensated in full for his loss, it will help cushion the financial blow. That was a very smart move on his part, I tell him.

“The kind of money that we’d spent on the facility was so huge it would’ve been stupid of me not to get it insured,” he laughs. “Look, anything could’ve happened — there could’ve been fire or theft. But we didn’t expect the rain would do this. I had never seen anything like this in my life.”

The flooding and the fatal blow

“We’re rebuilding the studio, but with a more refined approach,” says Ahmed Zawer. “We’ve contacted specialists so that we are protected by future rain.”

But there was also help from an unexpected source outside the city. Seeing how the musician community in Karachi was suffering, Lahore-based Zulfiqar ‘Xulfi’ Jabbar Khan, the creator and chief producer of Nescafe Basement among many other projects, decided to reach out.

“He told us that his basement had gotten flooded a few years ago as well,” relates Ahmed. “He guided us how to recover our equipment and because of him we managed to salvage and save a lot of it.”

How bad of a financial blow have they been dealt? “Our total loss was around 500,000 rupees,” says Ahmed. “We started a crowdsourcing campaign to help us recover that.”

The response has been good. “A lot of people have come forward,” he says. “People that know us, know that we’ve put everything we had into this. It’s our bread and butter. Because of the pandemic, we hadn’t already worked for six months. This [flooding] was like a fatal blow.”

A crowdfunding campaign was also set up by Quaid Ahmed from Sounds of Kolachi for Natasha and Hasan to set their studio, Laal Series, up again.

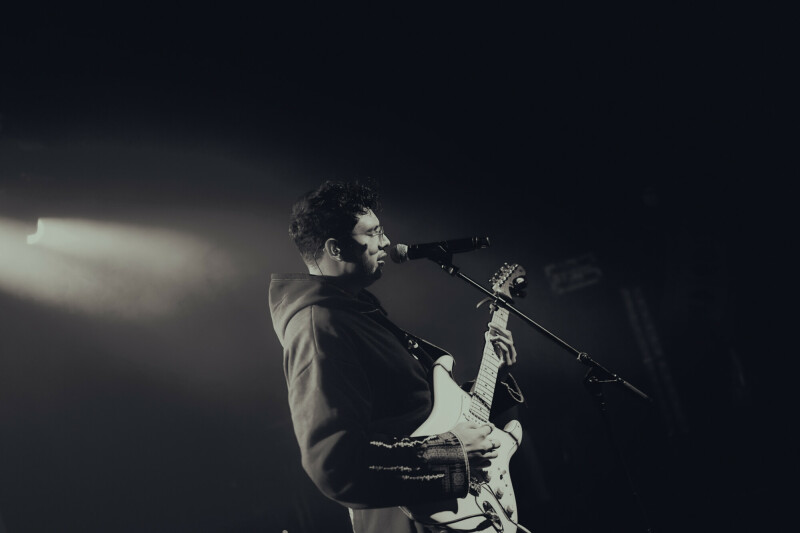

In the midst of all the photos and status updates online about how the urban flooding destroyed music studios, was a post generously offering unconditional help. Musician and producer Saad Hayat announced that his studio was open to any artist whose studio was wrecked and who needed a space to finish their project. All they needed to do was book a time slot.

“Saad’s gesture of lending his studio for free was so pyara [sweet],” says Natasha. “We were expecting the government to help us. But all these people who are on the same level as us — who are all [themselves] struggling — reached out to help us in our difficult time. What he’s done is beautiful."

“I’ve used his studio thrice for my work,” she adds. “I know my studio is flooded but my work won’t stop, so I’m in a good place now. I would’ve ended up in a mental asylum otherwise.”

She wasn’t the only one. “I’m at Saad [Hayat]’s studio right now,” laughs Ahmed. “We had a lot of projects going on. Saad put up the post the same day, thankfully. It was really nice of him. We’re in the same profession, so he understands that we all still have our deadlines to meet.”

“So now, we’ve taken all of our work to Saad’s studio. Hum uske studio ko apna samajh ke baithay hain (We’ve considered his studio as our own),” he jokes.

Although Saad Hayat’s studio is also in a basement, he told me that the fact that it’s remained relatively unaffected by urban flooding is a miracle. He managed to reach there in the middle of the rains and found some flooding from one side and cleaned it up just in time. Saad then spent the entire night in the studio cleaning up any water that was coming in. But others weren’t as lucky.

“I told everyone they can use my space until everything gets back to normal,” he says sounding embarrassed at even having to talk about this. “It’s the least I could do.”

That’s more than most.

Published in Dawn, ICON, September 20th, 2020

Comments