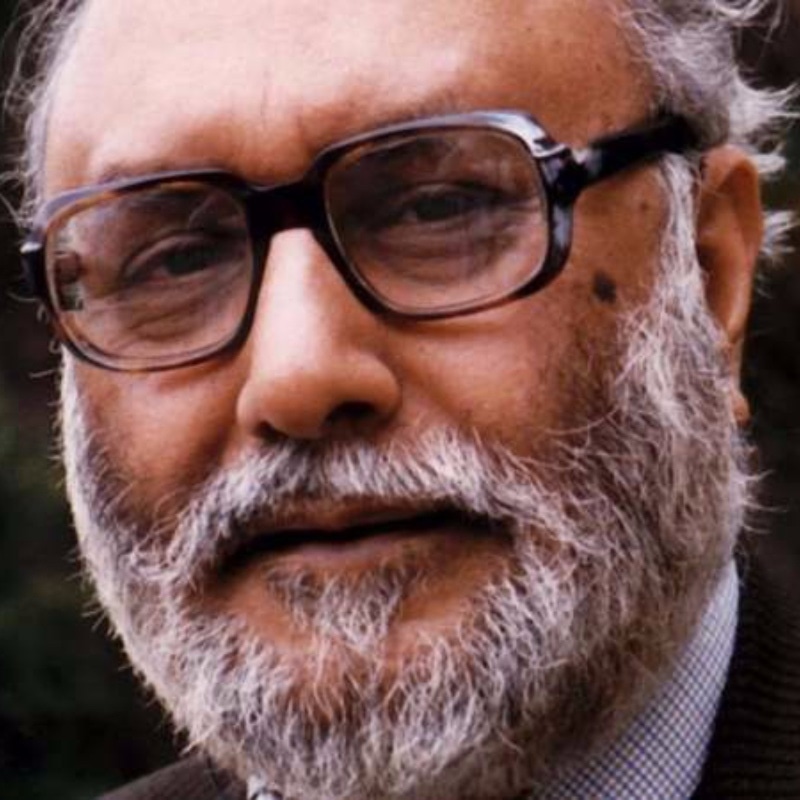

New novel Pureland is inspired by Dr Abdus Salam's journey from a village to Nobel prize victory

Landing in the US at the age of 18, Zarrar Said was all set to pursue a degree in physics. Lost in the headiness of college life and the beauty of youth he discovered an uncomfortable reality – Dr Abdus Salam, father of Pakistan’s nuclear program, an Ahmedi who won the Nobel Prize in Physics but was shunned by his nation.

Fascinated by this man who hailed from a village in Jhang, Said found himself on a journey leading up to his debut novel, Pureland.

“I was obsessed with his life and surprised that not many people had actually heard about him I found him universally appealing. He had never seen a lightbulb till the age of 15,” explains Zarrar of his inspiration. Feared by his father to be a mute at the age of three, Dr Salam was taken to a local soothsayer, a Pir who told his father that he was a gifted child and that one day he would speak so loud the entire world would hear him.

Sometimes all it takes is a little faith.

Although inspired by Dr Salam, Pureland is a fictional story about a village boy Salim and how he rises from the mud of his village to becoming a Nobel prize winner. It is a fictional tale filled with remarkable characters who turn by turn illustrate how societies falter and destroy themselves through a historical lens.

An extraordinary story, it is a beautiful fusion of rural and urban life spanning elements that shape lives and carve destinies including love, self sacrifice, destruction, identity, spirituality, suffering, ambition and hatred. Pureland opens a new chapter in literary fiction in Pakistan. While rural life has been documented in fiction and on television there is always the feeling of it being caricaturised and that Pakistani literature was never going to move forward from the usual tropes of a fallen woman, honour killings, terrorism. Zarrar’s book finally breaks the mould.

Zarrar weaves a narrative about the realities and absurdities of South Asian culture – often lost in translation – with great wit, cutting observation and beautiful prose.

“We cannot be culturally monogamous. A human being is multi faceted. To differentiate based on ideology is the most absurd thing,” says Zarrar

Sparkling with magic realism that nods to Salman Rushdie with V S Naipaul’s deceptive simplicity, superb satire that pokes fun at Pakistani idiosyncrasies and borrowing heavily from defining historical and cultural events, Said spans a tale that offers a delicious view of the awkwardness of being stuck in a post colonial country that the urban dwellers are prone to romanticise and the rural masses are left unable to comprehend, let alone experience.

Consequently, he offers villagers for whom life is to be taken literally with names like Cut-Two Naii, Pappu Pipewalla and Khassi Kasai. In contrast, when Salim is adopted by General Khan and starts a new life in the city of Lorr – again, a poke at how people are prone to speak colloquially – he is sent to the elite school, Blisschesterson (where cricketing fellow Mitti Pao eventually finds a career in politics).

Picking up on the South Asian leaning towards spirituality he juxtaposes how the rural interpret religion and spirituality when Salim is taken to the Floating Pir who predicts Salim’s future somewhat ambiguously. Keeping up with the continuous theme of parallel interpretations spirituality finds itself in an urban context in a slightly more refined but misunderstood form in the shape of two brothers Khalil and Gibran, neither of whom lives upto the peacefulness of spirituality but interpret faith in their own destructive ways.

Offering female characters who sparkle in their own right whether it is the headstrong Laila Khan or the evil Witch who exerts control over the Khan household, Zarrar also breaks the stereotypical assumptions that females are just sitting around lamenting their lives. They’re fighting for control over destinies – their own and others – and yet, in their own stories are they heroines? Or are they expected to pay a higher price even for what is the simplest of things like love?

Through Salim’s life the reader is taken on a journey of how societies thrive and lose when they reject their own in their blindness for glory confusing it with hatred. “The theme is that societies suffer from the prejudices they keep,” says Zarrar.

At a time when the world is war weary and Pakistan faces tougher challenges with heroes far and few between, this is a most necessary book that reminds us it's time to find the 'magic' we have all lost on a national level.

The novel is a literary journey through time, a journey that makes one weep of what has been lost and the ultimate destruction that reduces mankind to nothing but bloodlust. It is through this journey that one sees the transformation of Pureland’s characters.

“A human being is multi faceted. To differentiate based on ideology is the most absurd thing,” says Zarrar. Perhaps this is why he writes the story as magical realism. “We cannot be culturally monogamous. We are storytelling creatures and the way we tell our stories is magical. But magical realism is not just angels and demons, it is deeply rooted in reality,” says the author.

Loss of magic is the point Zarrar seeks to make through the various characters’ transformation. Connected through varying relations, touching on differing levels of achievement and success, the end result is that without magic in lives – in human form or other - there is nothing left and as a collective whole, a society will crumble.

“Dr Salam's life was full of magic,” adds Said. And what a magical journey it was. Being the last recipient of the Indian Peasants Fund (because World War 2 broke out) paved the way to an academic career in Cambridge. Still success eluded him as he struggled to have his papers published at times and was burdened by the fact that he was a Pakistani in a discipline dominated by Europeans and Americans. He eventually returned to Lahore where he was made football coach at Punjab University. His ultimate victory as a Nobel Prize winner was preceded by many hardships and rejections.

“At the Lahore Literary Festival, in the middle of my session, this European man came stood up and said that he was in Lahore teaching science. He was from Abdus Salam’s International Centre for Theoretical Physics. He mirrored the notion that Salam still gives back to his country even after his death; a country that didn't give him anything in return,” recalls Zarrar.

At a time when the world is war weary and Pakistan faces tougher challenges with heroes far and few between, this is a most necessary book that reminds us it's time to find the 'magic' we have all lost on a national level.

Comments