'Vinod Khanna held our hand when we needed him, but we let go'

I was five or six when I met Vinod Khanna for the first time. He was a friend of my father’s and not only one of the best-looking men I would ever lay my eyes on, but also one of the most generous.

I remember driving with my father and him to Pune and the Osho Ashram in his newly-acquired Mercedes Benz. That was the first time I sat in a car that expensive. I still remember the fragrance of the new leather that assailed my senses as I climbed into the backseat and the clicking sound of both his and my father’s malas (bead necklaces) as we sped over bumps.

Dawn broke as we stopped to refuel. My father and Vinod — as he insisted I call him — lit a cigarette at a distance. I meandered over to a pile of debris where I found a blue and gold Monarch butterfly, with one wing intact and the other crushed. I lifted the butterfly gently and took it with me for the remainder of my journey. The gold dust came off on my fingertips and I moved my hands around excitedly saturating the air with it. I felt like a fairy, with gold dust swirling around me and settling into my ringlets. “Look Papa, magic dust!” I exclaimed. “It will fade,” said my father. “Just like everything else.”

Outside, the starkness of the Western ghats revealed itself in the sudden harsh daylight. It was like how poet Robert Frost described it, ‘So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.’

Vinod Khanna held our hand when we needed him, but we let go. Our attention wavered. We forgot and it took death for us to remember.

On the 27th of April 2017, the day Vinod passed away, the Indian Film Directors’ Association Mumbai had organised a Master Class with my father. He had reluctantly accepted the invitation and stated, from the podium at the outset, that Master Classes only served the objective of contributing to the myth of the filmmaker. After two minutes’ silence in the memory of the icon who was no more, he began his conversation with a candid confession.

“I attribute my success in this dog-eat-dog world to Vinod and not my non-existent talent,” he began. “Had it not been for the generosity of this lion-hearted man I wouldn’t have been rescued from the garbage bin the film industry had hurled me into after my disastrous start. They say there’s no dearth of talent but there is a scarcity of talent to spot talent.” It was Vinod who, despite my father’s disastrous box office record, had told the producer to take him as a director. This was a new lease of life for him.

Vinod Khanna had made his foray into the world of movies in the late 1960s and ’70s with the legendary Sunil Dutt. However, it was the legendary filmmaker Raj Khosla’s musical dacoit drama Mera Gaaon Mera Desh — in which Vinod played the blood-thirsty Jabbar Singh — which launched him into the hearts of cinemagoers all over the world who loved Indian movies. My father who, at 21, was a third assistant and a production head on that film, says that it was here that the seeds of their friendship were sown, which bloomed and then withered as all things in life do.

Not many know that my father had joined the fast-growing commune of Bhagwaan Shri Rajneesh — who later became known as Osho — after tasting defeat in the fiercely competitive entertainment world.

Rajneesh claimed enlightenment was possible through sexual consummation. But my father became disillusioned with what the godman was promising and not delivering. So one day he broke his mala and flushed it down the toilet. One memory is still fresh in his mind, of his returning home after meeting Vinod in Filmistaan Studio and narrating to my mother about how Vinod had carried the message of Rajneesh who had pleaded with my father to come back to him and re-stitch his ties with the commune.

Lest the wrath of God fall on him, my mother — who seldom intervened in his private or professional life — had told my father that “if Vinod Khanna is scared for you then you must reconsider being a renegade.” But my father being who he is, had told her that the page had been turned and there was no going back. The fairytale that godmen deliver eternal bliss and save you from the aches and pains of life had ended for my father.

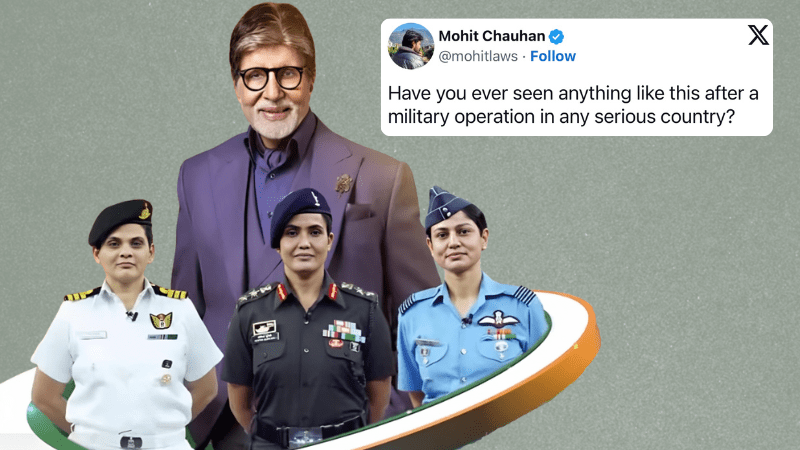

But sadly it never ended for Vinod who aborted his flourishing career and left with Rajneesh to go live in Oregon in the US. At that time Vinod was the only contender to Amitabh Bachchan, the ‘Big B’, with whom he had done innumerable films such as Parvarish, Khoon Paseena, Amar Akbar Anthony and Muqaddar Ka Sikandar.

The chatter in Bollywood those days was that the only person who could challenge Amitabh Bachchan’s dizzying climb to the top of the heap was Vinod Khanna. Alas, what happened is another tragic tale. But the truth is that these two buddies, my father and Vinod, became strangers despite sweet memories and remained that way because they differed radically not only on the metaphysical issues of life, death and whether anything endures after the physical form crumbles into dust, but also in their political ideology. They remained cordial but it was obvious that the glue that once kept them together, which was that of enlightenment and enduring peace, had evaporated. They drifted apart.

My father and Vinod became strangers and remained that way because they differed radically not only on the metaphysical issues of life, death and whether anything endures after the physical form crumbles into dust, but also in their political ideology.

I have other memories of Vinod as well. On my ninth birthday, I was in quarantine on account of a nasty bout of chicken pox. I was not permitted to interact with other children who might be susceptible to the virus and spent the day with my parents in our Pali Hill apartment. The only visitors I had that day were Vinod and a friend of his from the ashram. They collectively sang Happy Birthday and added much cheer to the day.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining was a rage back then so Vinod and my father did Jack Nicholson impersonations for me, each stating vehemently that they were better than the other. I have many Polaroids saved from the day. Suddenly, they hold new meaning.

I also remember accompanying my father to Vinod’s wedding (his second) with Kavita Daftary in 1990. I ironed my hair for the first time in my life, to appear presentable for the occasion. He greeted us warmly and looked genuinely happy to see us.

I also remember being on a cruise ship in 1995 with him, Shah Rukh Khan, Kumar Gaurav and others from Los Angeles to Mexico with rich, star-loving NRIs who had paid top dollar to sail on the seas with their favourite Bollywood stars. We were expected to mingle in the day but were provided a stateroom with an open bar where we could go and unwind when we needed time off from the posing and preening. I walked into the stateroom late one night to get myself a nightcap and there was Vinod, talking with great passion about the afterlife and if it existed at all. I grabbed a couple of miniatures and went back to my room, but the manner in which he spoke lingered in my head. Even among those more interested in frivolous conversation, he was grappling with his own soul.

Vinod is also linked to one of my favourite songs from my father’s film Jurm — it is a song that has given many people hope as well made many more cry. It’s a song that my father sang to me in a Benaras banquet hall on my 40th birthday. ‘Jab koi baat bigarr jaaye, jab koi mushkil parr jaaye, tum dena saath mera o humnawa ...’

The narrative of Vinod Khanna came to an end after a long battle with cancer which had been kept a secret by his family. The response by Bollywood was overpowering, especially the senior lot which had witnessed his rise and known and worked with him. Rishi Kapoor — who had worked with Vinod in Amar Akbar Anthony — lambasted the younger lot of actors and actresses for being callous and not showing up at his funeral.

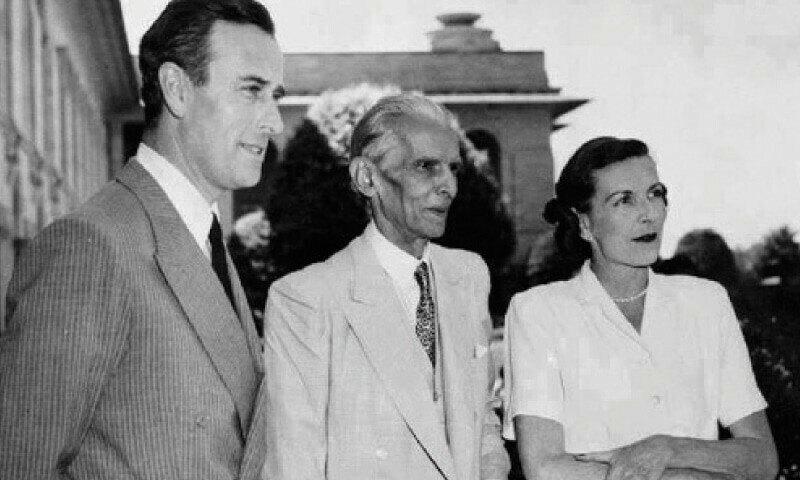

I was assaulted with my memories of Vinod on the day when I saw my father’s tweet with a picture of them when they were both very young. He’d written “Those were the days my friend, we thought they’d never end, we’d sing and dance forever.” That tweet seemed even more poignant because I read it whilst visiting family and friends in Pakistan. Vinod had been born in Peshawar.

Related: I'll support any cultural activity between Pakistan and India, says Mahesh Bhatt

There are more than a few people Vinod had been a lifeline to without expecting anything back — in one instance he helped someone get their sister married; in another he helped someone buy a house. That latter someone was none other than my father who was torn between two women and was guilt-ridden after having walked away from my mother. He was bailed out by this gracious man who helped us get our first flat which became an oasis for me and my mother.

“Ho chaandni jab tak raat / Deta hai har koi saath / Tum magar andhero mein / Na chorrna mera haath…”

He held our hand when we needed him, but we let go. Our attention wavered. We forgot and it took death for us to remember.

Originally published in Dawn, ICON, May 7th, 2017

Comments