'Jamil Naqsh was not political at all'

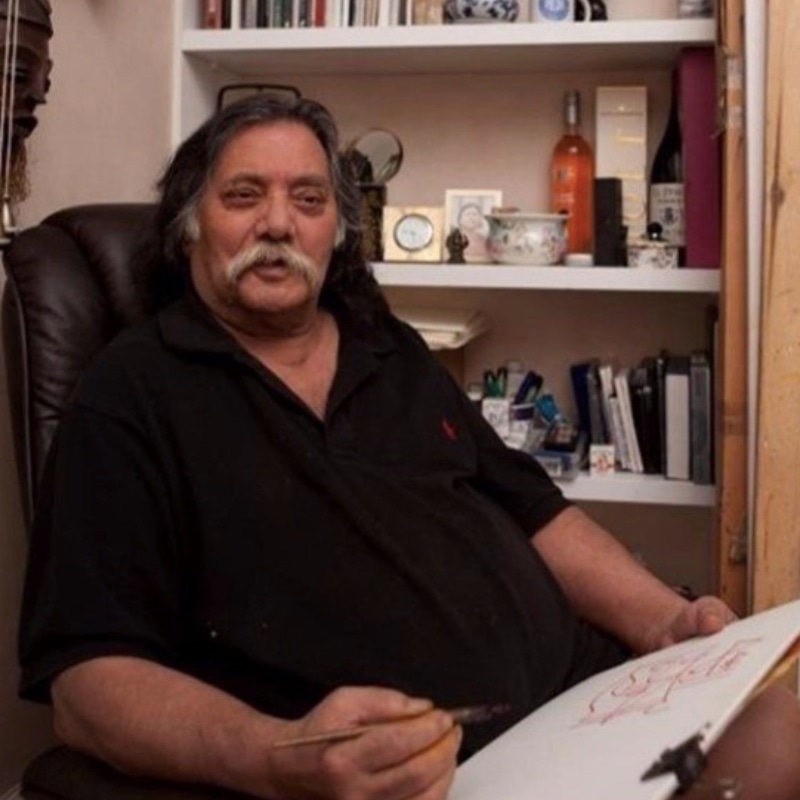

In the sanctuary of his home in Lahore, Mian Ijaz Ul Hassan — prolific painter, art critic and art historian — is surrounded by framed canvasses showcasing the strokes of his brush. As articulate as he is expressive, Hassan is unaffected by a sense of urgency that afflicts present-day discourse on art, yet is perhaps one of the few whose work and ideas remain up-to-date.

A student of Aitchison College and Government College, Hassan proceeded to study painting at the prestigious St. Martin School of Art in London for a year in the 1960s. He then pursued a Bachelor’s in English from St. John’s College, Cambridge. Upon his return, he joined the National College of Arts as a Professor.

Hassan has been in the forefront of Pakistani painting for nearly half a century, giving him the unique privilege of witnessing the evolution of the art scene over the decades; an insight he documented in his book on the works of other contemporary artists, published under ‘Painting in Pakistan.’

As a recipient of the President’s Award for Pride of Performance 1992, the highest national award in the field of art, as well as the Sitar-e-Imtiaz, Hassan is a nationally acclaimed painter, who has exhibited his work all over the world.

More importantly, as a contemporary and a friend of Jamil Naqsh, the iconic Pakistani artist who passed away on May 16. Below is an interview of Ijaz Ul Hassan reminiscing Jamil Naqsh, art, modernity.

Images: I believe you knew Jamil Naqsh well. What was he like as a person?

MIH: He was my contemporary. As you know, he was a student of the National College of Arts, but he didn’t complete the degree. Thereafter, he was located in Karachi for most of his life where he first worked for an advertising company. I actually knew of him earlier when I had met him in the late 60s. But it was later that I came to know him well. We were quite cordial. Although we met infrequently because he was all the way in Karachi, we were friends.

But as things would have it, I met him in London recently about three or four months ago and spent an entire evening with him. I didn’t know we were going to lose him. But it seemed like he wasn’t very well.

He was basically a very aloof person. And I think being in London enhanced his solitude. He was never a big talker, but a very cordial and a very courteous person, and in that sense, a profound person and a profound painter. And that showed in his work, it was quite reflective, and not demonstrative in a coarse sense of the word.

Images: Would you know of his early days in Pakistan? And could you share something about his personal life, which we don’t know much about?

MIH: Neither do I, to be honest. I think I never pried into his personal life, I only knew him as a great painter. And his period doesn’t really fall into the early period of Pakistan; it was actually the mid 60s onwards. Maybe we can talk about what aspects of his work interest you.

Images: He had a very distinct style of painting, which was reflective of a technique he developed for himself. What were some of the influences that informed his work?

MIH: That’s more of an inquiry. You see, largely for all painters your intentions determine your expression, whether you’re a writer, poet or a painter. There are some who write a ghazal and then there are some who write a nazm; they’re not the same. Nazam has a greater sense of urgency and immediacy and it is current, while a ghazal romanticises and idealises; you wouldn’t see Jalib narrating a ghazal. In that sense, Jamil Naqsh’s work did not deal with current issues. I don’t think you find in his work, in a specific context, any socio-political issues or concerns. And nor is he preoccupied with any psychological nuances.

I was reading a statement; it was perhaps in Dawn, that he was the ‘last of the moderns’. I did not agree with it and thought it was a short-sighted statement. Because modernism is neither a style, nor a product of a manifesto; anything which discards outdated modes of expression or thought is ‘modern’. So, you can live today and yet not be modern. And there are a lot of modern painters, even young people these days can be called modern.

Images: But young painters these days like using the term ‘contemporary’ rather than modern.

MIH: Yes, contemporary is a safer term, and a more realistic term. Because in the contemporary world, there are a great diversity of things; there are people, there are wars taking place, at the same time there are people talking about saving our mother Earth, talking about pollution, and all manner of things. So our contemporary world is quite different from that of Aristotle or even say, Picasso. Then, contemporary art, or even ‘modern’ art does not fall into one region. Our contemporary style of painting is very different from the paintings of the Japanese or the Americans or the British.

Images: Was Jamil Naqsh’s work informed by other modern painters or styles?

MIH: I think at some level all painters can be called ‘thieves’. And anything that they deem useful, they put in their pocket. But to say someone might have a European influence isn’t right. Nobody talks about how the Europeans were influenced by African culture. This has become a cliché.

I think, Jamil Naqsh consciously studied miniature painting, then he left that. What we don’t realise is during his association with Haji Sharif, he obviously learned the basic techniques, which was not just drawing a straight line. There’s something called ‘Pargatkaari’, which is how you build shadows. During Jahangir’s period there wasn’t a lot of attention given to shadows in miniatures. And since water colours were used, you couldn’t create gradation.

But there was a desire to ‘express roundness’ and shadows. And how could that be done? It was done by putting small dots to create thickness and thus shadows. And it was quite a meticulous exercise.

People also talk about Jamil Naqsh drawing pigeons and doves, this is like saying Michelangelo would make nude forms of wrestlers and athletes. It’s absurd to say so.

And how do you put a dot? You have to use your wrist to out a dot, and for that, you would need a nimble wrist to be able to do it. Not the fingers, you need the wrist. And very few people realised that one of the reasons the Japanese were able to make the transistor radio is because they had nimble and flexible wrists, that they would use to write their language. So soldering was easier for them than for someone like you and me.

So, if you look at the application in Jamil Naqsh's earlier work especially oil paintings, he worked on the surfaces to create texture and volume, using the same technique. It is not filling of paint; it is filling the surface of the canvas to create nuances of shade and colour. This created a great unity in his picture surface, which was quite remarkable.

And one of the concerns of modernism during the period of abstraction and later not so strictly followed, was to avoid the sense of illusion. That if a canvas is flat, therefore things should appear flat. So you find in his work a sense of flatness of the picture surface.

Secondly, it was the way he used the line, which was very precious to him, and he used it in multiple ways. You also find him scratching it in thick paint. It was precious to him in delineating objects, forms in Persian, Mughal-Persian, Chinese and Mongol traditions. So you find that the ‘continuity of line’ is very important in his work.

People also talk about Jamil Naqsh drawing pigeons and doves, this is like saying Michelangelo would make nude forms of wrestlers and athletes. It’s absurd to say so. He also liked delineating the figures of women. One reason he would draw pigeons could be because it wasn’t a captive bird; it is free to fly around.

The manner that Jamil Naqsh paints the nude, was not for men to lust after. Most of his nudes are women who are stocky, have a round face, with eyes full of life. They’re either not very sensuous or erotic.

His relationship with this subject is very close and intimate. His work, 'Woman with a Pigeon', can be said to be very interactive. And they overlap each other; sometimes you can see one through the other.

If you want to explain Jamil Naqsh, it could be said about him that he was an abstract painter. He abstracted things and simplified them. He was concerned with form, but, not necessarily in terms of weight but in terms of shape. And shapes can be also broken up into various sections, and he broke them up originally in smaller sections. And many of these sections overlapped. In his process, the earlier figurative forms he made were very static and primitive. And then, they break up, and the colour becomes more subdued and the forms become intricate, not heavy or coarse, but delicate.

Images: Could you comment on the style of nudes Jamil Naqsh would paint?

MIH: One finds that he paints the nude considerably. Kenneth Clark talks about the naked and the nude, and that the naked is artless but the nude is a form in full possession of itself. But, there are others like me, who disagree with that.

The traditional nude painting, whether you see it in the Renaissance or otherwise, is a delicate woman who is being offered to the viewer, and is there for the viewer to lust after. Whereas the nude woman is somebody you’re prying into, she has not offered herself to you.

But I think the manner that Jamil Naqsh paints the nude, was not for men to lust after. Most of his nudes are women who are stocky, have a round face, with eyes full of life. They’re either not very sensuous or erotic. And he gets away with it. Even in Shakir Ali’s work, he painted nudes but they are seldom erotic, inviting you to lust for women’s bodies.

Jamil Naqsh was not political at all! In fact, the whole generation was not political, and in fact, took pride in it.

In Jamil Naqsh, I would say, his entire elements are sensuous —the way he paints, his strokes and colour— but he doesn’t particularise. In his earlier work, if you see his development, his work is more stylised, and then it becomes more abstract and complex. I don’t think he treats his pigeons any differently than the way he treats the nude woman.

I recently went to the Jamil Naqsh museum, and his family was also there, I was looking at the works which were included in this exhibition, inaugurated by the president. While a lot of his work was based on line and colour and were not figurative, but, since the inspiration of this show was the ‘Indus woman’ or better known as the 'Fisherwoman of Mohenjo Daro', where you found chocolate dark colours of the Indus woman. Jamil Naqsh was using signs from the seals and the artifact of the dancing girl of Mohenjo Daro; which the Indians never returned.

I’d also like to add, Naqsh belonged to that era of painters, a time when there were no galleries. Commercialism was not as stark as it is now, and art was not sold easily. Nowadays the artist doesn’t know the collector but knows the galleries. To this day, I am very particular about who I sell my works to. And unless I am pushed, I hardly ever give my work to foreigners.

It’s like giving your offspring to somebody; you need to be careful about who’s going to adopt it. In the development of Jamil Naqsh’s work, nowhere does it say that he’s trying to market himself. And that is very important. Painters these days start with an exhibition in Delhi, Dubai, and London— and more importantly pick up the ‘jargon’ of the art world. Art has now become a consumer item, and the galleried have taken over, who come up with the jargon to sell a work of art.

For Jamil Naqsh, art was an act of passion. And I think his basic impulses were very indigenous. I can’t think of a European painter when I look at his work. And that I think speaks a lot for him. And young artists should emulate this, they must evolve their style, but not consciously. Not everyone can have the same gait as Marlon Brando, if you emulate his unique style of walking, you’d look like a fool. You learn from others, so that you yourself can walk in a straight line.

Images From what you’ve told me it doesn’t seem like Jamil Naqsh was a very political person. But, sometimes our artists are canonized in a way that their work becomes political. Some sources have even alluded to his ‘political activism’. Was he a political/politically conscious person?

MIH: Who has said this? He was not political at all! In fact, the whole generation was not political, and in fact, took pride in it.

Images: One last question, could you share some interesting stories about Jamil Naqsh? Something that would speak of the personality behind the art?

MIH: I really can’t say. All I can say is that the contact between myself and JN was intense. Once, a friend, Irfan Hussain and myself went over to see him in Karachi. My friend liked a few of his developed sketches. After I came back to Lahore Naqsh called me up and said he had gifted the sketches to me for my friend. He was that kind of a person.

In fact, let me share with you my ‘last embrace’ with him. And when I learned of his death, I wrote a note also. I’ll pass that on to you. I sent it forward to his family also.

“Jamil Naqsh will always be remembered for he is indeed a legend. He was not merely a ‘Painter’s Painter’, but an artist that all art lovers cherished. His work vividly spans over sixty years. He was one of our abstract painters who was an accomplished draughtsman. He delineated the line and manipulated structures of forms with immense skill. I am greatly saddened to know that he has gone. What an artist! What a man! He was extraordinarily gifted, courteous and gentle. He was a dear friend; an irreplaceable loss for us all. May Allah bless him and hold him in His fold. I also pray that Allah grant his family peace of mind and the strength to bear the loss.” — The Last Embrace by Ijazul Hassan

Comments