Pithas, machi bhaat and the heavy burden of migration

I opened the fridge to see two pieces of samosas on the lower shelf. Except this samosa was white and the covering had a glossy finish to it. The covering was also soft when I poked it, unlike a samosa, which is crispy. “Then it definitely is not a samosa,” I thought to myself. As a 10-year-old who had recently moved in with Nana Abu and Nani, the closest association I could make to this newly discovered food in my fridge was to that of a samosa, even though a dumpling would have fit better, but dumplings only gained traction much later in my teenage years.

“What is this food then? Why haven’t I been asked to try it yet?” I wondered. A call to food is usually given out by Nani from the kitchen, but the birth of this white samosa was kept a secret. Maybe this food is only for adults? Or for pregnant women? Except that no one was expecting in my house. I shut the door to the fridge and continued on until, much later, I overheard Nani calling this peculiar looking samosa a “pitha”.

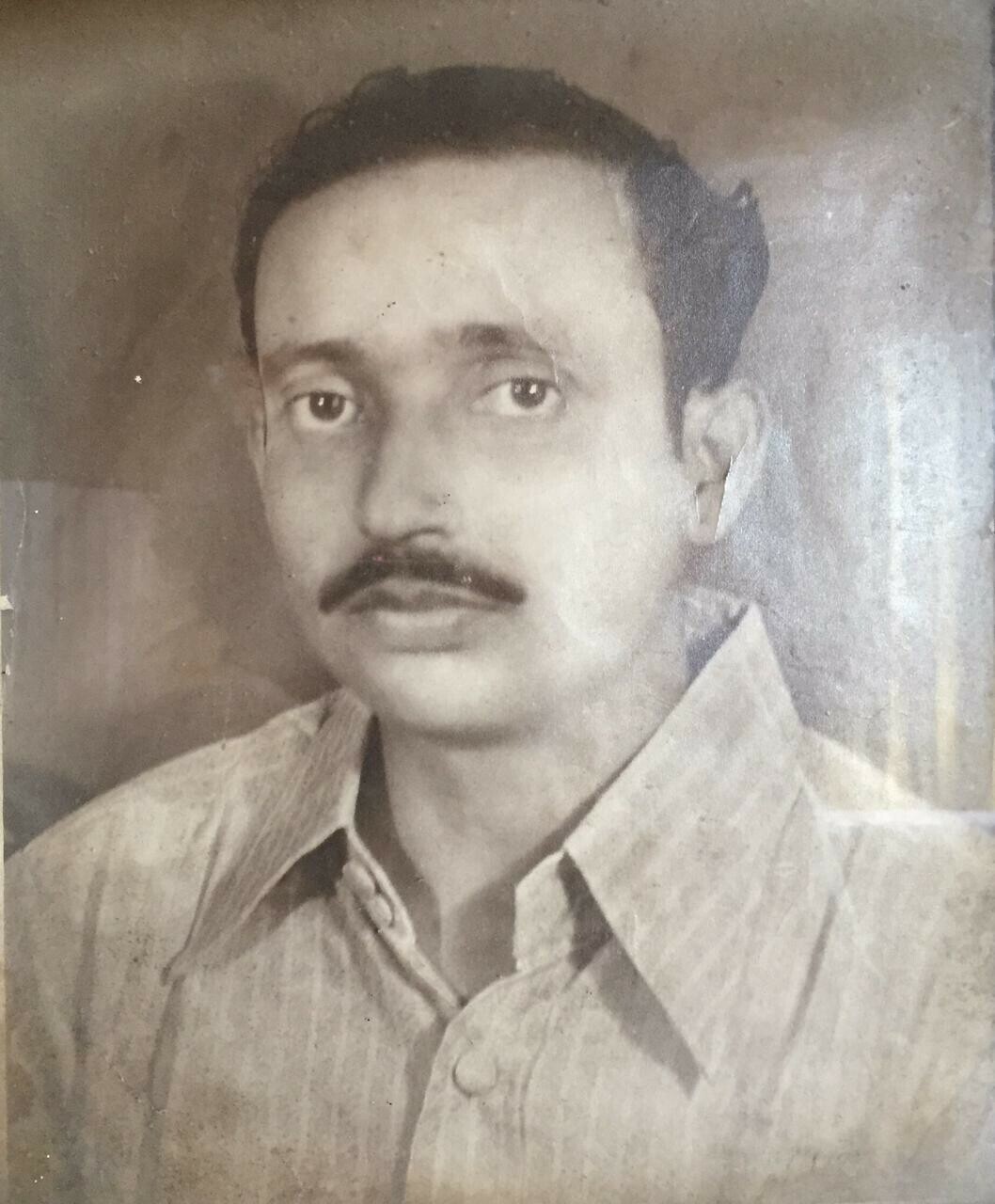

My grandparents migrated from Bihar, India to Dhaka, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1947 and spent most of their adult lives there before migrating again to Karachi in 1971. They made sure that their grandchildren were cognisant of their roots and culture — the one they fought to incorporate in the very fabric of their lives. Hence, we were served history lessons alongside food at the dining table.

But despite all their efforts, something seemed off in their discussion when it came to Bengali food. Nana Abu would rejoice at the mention of his time spent in Dhaka and the machi bhaat that he missed until he passed away in 2016, while Nani always made pitha in seclusion. It was made and devoured but never openly talked about. It seemed like a part of history that she did not wanted to admit — until very recently, when I invaded the kitchen and followed her through the pitha making process and tried to disassemble history and food.

Muscle memory

Nani poured rice flour from a plastic bag into a big bowl and added hot water while slowly kneading it with her hands. She kneaded the rice flour until the consistency toughened.

“The pithas here don’t maintain their shape, they easily get cracks or break down when you boil them,” she told me.

I asked her what could be a probable reason, to which she replied that the quality of the rice differs greatly. ‘Joshi’ rice flour was used in Dhaka and was very famous, apparently.

Being an agrarian country, rice is a staple food across most regions in Bangladesh and thus pitha celebrates the arrival of the harvest. There are many different kinds of pithas — bhapa pitha, nokshi pitha, patishapta pitha, puli pitha, etc. All of these pithas differ in their filling, shapes, sizes and the techniques with which they are cooked but the covering, which gives pitha its characteristic feature, remains the same. Interestingly, the pitha that nani makes is just called a pitha without any pre-fix. The name got lost somewhere during the journey across two borders but the memory of the food remained in her mind and within her hands. What she makes now is from muscle memory.

“Who taught you how to make pitha?” I asked her. She laughed and then responded, “That is a very difficult question! I don’t know, I just saw everyone make it and so I started making it. But I remember my khala used to make it.”

I tried to inquire more about her khala and if she lived with them, to which she replied “aaray she was also my mother in law!” which made me laugh at my foolishness but I reoriented my gaze towards the pitha.

During the course of our conversation, Nani took out a chunk of the kneaded rice flour and rolled it between her hands, flattening it out in small circles. She took out a tablespoon of the filling that she had prepared and kept in the fridge overnight and placed it within the disc. The filling was made from diced onions and green chillies, powdered red chillies, white cumin seeds and black pepper. The main constituent was, however. daal masoor and daal chana soaked in water and then blended to give a foamy texture. Some pithas were also filled with coconut and jaggery upon fervent demands from outside the kitchen.

Once the pithas were stuffed and sealed, they were put into boiling water and cooked for about 30 minutes.

The pithas looked stiff and swollen when Nani took them out of the saucepan. They were then left to cool down.

Food for thought

A more popular Bengali dish that would be easier to recognise is machi bhaat. Fish and rice, both staple foods in Bangladesh, come together in different forms creating a new harmonious flavour each time in this dish. While bhaat literally translates into rice, the way it is cooked largely differs from the way it is cooked in Pakistan. The rice is mushy and soft in a way that allows the rice grains to clump together easily. It is eaten with fish — the most popular in my family is the fish curry that Nani cooks.

A friend’s uncle who lives in Karachi also recalled paanta bhaat, which is made by submerging leftover rice in water and then eaten for breakfast. Salt, lime and roasted red chillies are added for taste but the quantities vary according to taste and requirement. Paanta bhaat seemed like a new dish to me, something that I had never heard of before until I did a quick Google search and saw a picture of a dish that resembled something Nana Abu ate occasionally. It is, however, quite fascinating that in his version of paanta bhaat, he replaced the roasted red chillies with roasted dundicut peppers — a variety of chilli native to Sindh. His paanta bhaat was in fact an amalgamation of Bangladesh and Sindh — two lands that gradually trickled down to his plate.

I did, however, realise that his paanta bhaat was different in more ways than one. The rice wasn’t the same quality and neither was it soaked in water for as long as it should have been for a typical version of the dish. It was, instead, his way of reminiscing about a past left behind.

Mixing cultures and blending foods

“Kids in Bangladesh are trained from the very beginning to eat fish without having to take out the bones by hand. They eat the fish while gathering the small bones on one side of their mouth,” Dr Seraj Ud Daula, a senior pathologist from Karachi, reiterated what Nana Abu used to tell me over a phone call. His parents hailed from Bihar, India but spent some of their life in East Pakistan. He shared with me the food he saw and ate and the food that was able to make it across the border with them when they moved.

“Mangur was a popular fish over there which can survive out of water. It was mostly fed to people who were battling disease in hopes of them getting better. I don’t know how true that is though,” he said. Hilsa is a well-known type of fish that Dr Seraj deemed a cousin of Palla, which is bred and sold in Sindh. I liked how we have turned to a relative of fish as an alternative, signifying how the body migrates but the mind doesn’t — it looks for alternatives.

Suthki Maach is a spicy dried-fish dish, which, according to Dr Seraj, is a specialty of Bangladesh. “Not everyone can make it,” he declared. It was a popular dish during his time and while most people enjoyed it, for him the smell was a bit too peculiar.

A lot of people who had migrated to East Pakistan post 1947 had a hard time adjusting to the smell, which might be one reason why it did not gain much popularity within the non-Bengali population.

A taste of Bangladesh in Karachi

Once his analysis on fish came to an end, he told me that I could find all these fish and other native Bengali vegetables in Karachi’s Musa Colony. And so one day, I ended up in Musa Colony with Amma.

The street is narrow and packed — with both people and fish. The olfactory sensation alerts you of your arrival to the fish market far before your eyes do. Abu Tahir, who owns a shop there, was a Bengali who has been working in Musa Colony for the past five years. His shop was lined with baskets full of dried fish and shrimp of various kinds. On the other side were fruit, spices, a mould for pitha and an undershirt.

“This is from Bangladesh, that is from Bangladesh and even this banyaan (undershirt) is from Bangladesh!” he laughed.

The fish at his store are used to make chutney, curry or are sometimes even fried and eaten. A lot of people also buy them to feed birds in the winter. Most of his customers are either “Bengalis or Biharis because they have lived in East Pakistan and know the taste of this food,” Abu Tahir explained.

Despite being born and raised here, and having the rightful citizenship of this land, he said that “Pareshani hai (there are difficulties)” because of the discrimination they face. “If people get to know that a person is Bengali, they will taunt him about his language, about machli chawal, and make fun of him,” he said. Food is, in this instance, turned into a a weapon of discrimination, with some people also calling Bengalis “smelly” because of their staple diet of fish. Things may have changed over the years, but Abu Tahir said initially, Bengalis and Biharis were always targeted because of their association with Bangladesh.

Seizing the opportunity, I revealed that I too was Bihari and asked him about the food he ate at home. Puli Pitha stuffed with coconut, plain rice cooked without salt or oil and all types of fish was his answer. All of this is still cooked here, both in his home and mine.

The next shop was filled with fish, both dead and alive. Dilawar, a Bengali man whose family has lived and worked here for about 70 years, told me most Bengali customers prefer buying sweetwater fish, which are occasionally brought and sold here.

Raihu, Sol and Singhi were available at the shop beside his and people gathered around to see the fish moving and flopping about in a red basket as the shopkeeper fished them out of a water tank.

Sweet memories

While on the phone with Dr Seraj, I redirected our conversation to desserts — the most awaited course of any meal. Surprisingly, there wasn’t much to talk about. The answer to every dessert-related query that I may have had was “Dacca Sweets”.

It specialises in Bengali sweets and has branches all over Karachi. Bengali sweets that many people may have enjoyed in what was East Pakistan are readily available here and so the need to go through the tedious and meticulous task of sweet-making at home is greatly diminished.

Dr Seraj laid great emphasis on the meethi dahi (sweet yoghurt) from Dacca Sweets that I have also enjoyed over the years at home, saying that this yogurt has no match and that if someone dared to make this by themselves, they were bound to mess up. Having had the ever so famous meethi dahi from Dacca Sweets, I nodded in agreement and tried to keep the inevitable thoughts of the appetising meethi dahi, which comes in a mud clay bowl, at bay.

In contrast, is the far more popular rasgullah, which finds itself burdened with many die-hard fans. It is liked and enjoyed all over Pakistan, not just by people who migrated from East Pakistan. But is the rasgullah at par with what many people enjoyed in East Pakistan? “Not at all! It’s very different!” exclaimed Dr Seraj.

The rasgullah has changed, it is now “bigger in size, sweeter and less soft” compared to what he ate growing up. The widespread acceptance of this sweet may compensate for the alterations that have been made to it, because the community of people that have migrated twice and have brought with them various Bengali delicacies are still scared of discrimination. So a sweet paving the way towards harmony is a considerable step.

Mubashir Ahmed Khan, who has worked at Dacca Sweets for 17 years, told me that the shop was opened in 1984 by Farhaj, more popularly known as Guddu Bhai. The items were new but, most importantly, the sweets were different because they were less sugary than ones available locally. “The workers are all Bengali, and thus what you eat is the taste of their hands,” Mubashir told me. Commenting on the popularity of meethi dahi, he said the 150 bowls are made every day and they are sold out by 4pm. Among the most famous Bengali sweets sold at the store are malai cham cham, Dacca cham cham, moti cham cham and kacha gula.

Leaving behind everything but food

Despite the evident presence of Bengali food in Karachi, there are still a lot of questions about it that remain. Why does Nani have a hard time admitting this part of their history and culture? The question kept bothering me. Upon much persuasion, Nani told me that during her last few days in East Pakistan, Biharis were being tortured and persecuted by the Mukti Bahini. Her clothes and jewellery were stolen, people they knew had been killed and they were surrounded by terror. After fleeing the riots in Dhaka, they moved to Pakistan but the government was reluctant to rehabilitate them and most people would tell them to “go back”. Despite being recognised as Pakistani citizens, they were targeted in communal violence and thus chose to stay silent about their identity.

Both Nana Abu and Nani were left stranded between the power politics of two nations. And thus cooking Bengali food or even talking about it in Pakistan could have easily been labeled an ‘act of betrayal.’

Like her, many people refrain from talking about the time they spent in East Pakistan pre-1971. This is perhaps due to fear of judgment, coupled with the exclusion they had faced on both sides of the border. In East Pakistan, the Urdu-speaking population faced persecution and, later upon their arrival in West Pakistan, they were not welcomed due to their intertwined history with the newly formed Bangladesh — as a result of the prevalent anti-Bengali sentiment. This led to them shedding the few words and phrases of the language they may have picked up as well as their ways of life, which were now foreign to Pakistan. To be accepted back in this country, they had to prove that they were in fact part of the Urdu-speaking population and not Bengali.

While the clothes and language was shed and replaced, the food remained. It was made and enjoyed, albeit secretly. No matter how troublesome the past may have been for both sides of the border, the food we devour is a testament to our shared history and resilience. We will continue to make pitha and machi bhaat, even if the rice is not as soft, or as flavourful.

In the words of Naseer Turabi,

Woh humsafar tha, magar usse humnawayi na thi

Keh dhoop chayon ka alam raha, judaayi na thi

He was my companion, but we were not in harmony

Like the clouds and sunlight, together but as apart as can be

Header artwork by Radia Durrani/DAWN