Cataloguing Pakistani film industry's past to help its future

“We’re not doing enough for our next generation,” Shaikh Amjad Rasheed tells me as our tea arrives. “We have a rich history of films and filmmakers, who unfortunately very few know about and even fewer appreciate today.”

Rasheed is the Chairman of the IMGC Group of companies (producers of edible oil brands, textile manufacturing mills, soaps, detergents, etc) whose media label, Distribution Club (DC), produces and distributes a lot of Pakistani motion pictures.

In fact, DC doesn’t say no to movies at all. Good, bad, ugly, atrocious, they all eventually find a distribution partner with DC, because Rasheed can’t say no to filmmakers. He once told me that if he doesn’t support Pakistani movies, who will? The least he can do is get them to the screens. Whether they work or not, that’s their own kismet, he says.

However, our meeting isn’t about DC or their new slate of movies. Rather, it is about looking at the past — and hopefully learning from it.

My tea cup is shifted to the other room, where I preview snippets from a new interview show, titled Journey of Icons (no relation to this publication), in which veteran actors and filmmakers pour their heart out.

Film producer Amjad Rasheed wants to give back to his industry. An under-production interview show with veteran actors and filmmakers is merely the first step. Eventually he wants to create an independent digital film archive for Pakistan

Directed by Shehzad Rafique, a well-known director whose filmography includes Salaakhein, Mohabbataan Sachiyaan, Ishq Khuda and Salute, Journey of Icons has a nostalgic, heart-touching feel.

The show, I was told, was quickly wrapping edit and another season with Karachi-based celebrities was being prepped (the first season is Lahore-centric), and that a broadcast deal with DawnNews has been finalised.

“We’re not doing a regular television show,” Rasheed tells me. “Our guests are allowed to speak well past their time limit.” Although one episode is planned per artist, some celebrities have two or three episodes because they have so many stories to tell.

The teaser trailer, by itself, is longer than expected, and the line-up of guests shown in it is extensive: Iqbal Kashmiri (late), Nadeem Baig, Ghulam Mohiuddin, Syed Noor, Hamid Ali Khan, Nasir Adeeb, Shahid Hameed, Sangeeta, Zulfiqar Ali Aatre, Deeba Begum, Nisho Begum, Irfan Khoosat, Resham, Masood Butt, Hasan Askari, Altaf Hussain, Tafu, Arif Lohar, Shabnam Majeed, Naveed Nashad, Naghma Begum, Sania Saeed, Zara Sheikh and Hadiqa Kyani.

“There are no prefixed questions. Rabia Hassan, the show’s host, was told to not interfere,” he says. “She was instructed to let [the guests] speak of whatever they want to talk about.

“Iqbal Kashmiri was bed-ridden when we invited him for the show. Despite his illness, he came over and recorded an episode. It is his last appearance on television. He passed away 15 days later,” he continues. Having seen some footage, Kashmiri’s last interview is an emotional experience.

While a necessity, such a show isn’t really a novel idea, I tell Rasheed. Interview shows are produced by the bulk on television; some of them focus on both old and new celebrities alike.

The Chairman of the IMGC group smiles as he motions my attention to a preview brochure, whose second page has a big black-and-white picture of Shaikh Abdul Rasheed — Amjad Rasheed’s father — a journalist, producer and distributor who passed away in 1977.

“We have other businesses that do very well, but I have a passion for the industry, and this passion, this devotion, has been passed on to me from my father. I want to continue with this devotion as long as I live,” he begins.

The plan, he tells me, is not just to make an interview show. It’s but one cog in a much bigger machine. Journey of Icons, the show, functions as the first step in the creation and the curation of an independent digital film archive that would serve as an ultimate reference point for the people and the media industry alike.

Developing a film database

Since people aren’t in the habit of reading books, a web portal, with a film database, is being developed — a Pakistani IMDB of sorts — but it won’t be a cold, uninteresting source of reference. The site will have shows such as Journey of Icons and re-mastered version of movies, amongst other things.

One big problem that’s setting up a roadblock in Rasheed’s endeavour is the issue of copyright. Rasheed says that he’s reaching out to producers, distributors and representatives, but he’s finding out that some are not really seeing the bigger picture here. “When rights interfere, we can’t even showcase music or clips,” he tells me with frustration in his voice.

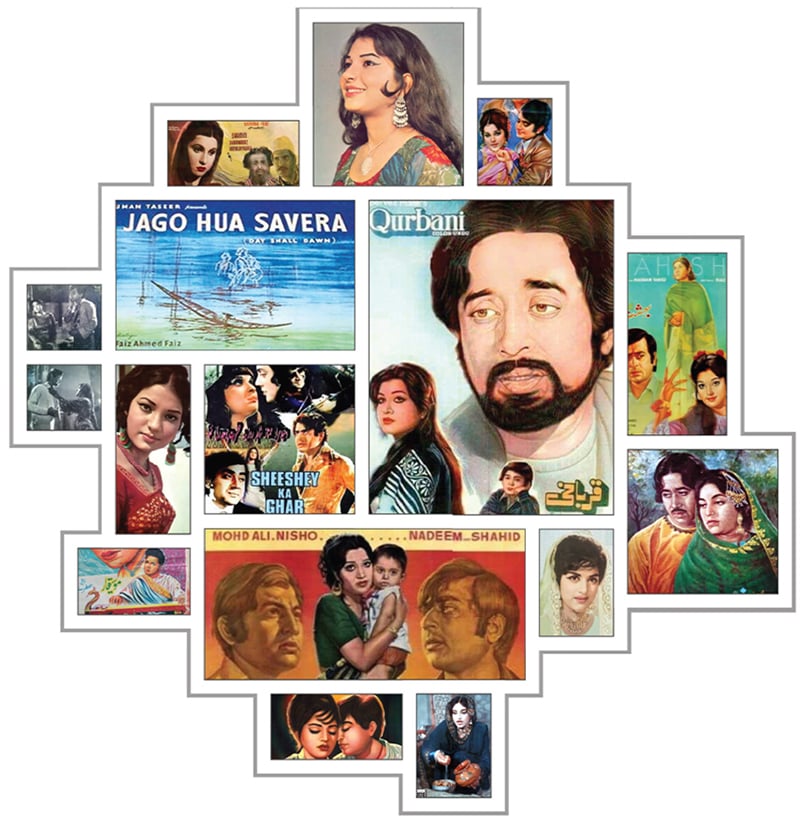

Rasheed did hit more home runs than not, though. He tells me of Jago Hua Savera (1959) by director A.J. Kardar, written by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, starring Khan Ataur Rahman. The film won awards at the Moscow and Boston film festivals, and is by far considered the country’s first serious attempt in making neo-realist cinema.

“My father released that film. It did excellent business in Russia,” he tells me. The producer in the UK has found a print with great difficulty, Rasheed confirms, and that he’s working on making it a part of his library.

Rasheed has also acquired Do Ansoo (1950). Starring Santosh Kumar, Ajmal, Sabiha Khanum and Alauddin, it is the country’s first Urdu language film to attain the Silver Jubilee status. Films such as these are inspirational, Rasheed says. “They had little facilities back in the day, yet the films told stories with characters and music, and managed to carry a strong message as well.

“I was at the Cannes film festival once, where I met an Indian producer who had made a library of artists and technicians, and he wanted some interviews from Pakistani artists and technicians. At that moment, I took it upon myself to create a library like this for Pakistan myself — but I won’t stop here,” Rasheed asserts.

“I’m already working on collaborating with international institutions who would be interested in including or showcasing content from our library,” he adds.

'Film industry is not a priority for govt'

But isn’t preserving film and cinema the government’s responsibility, I ask.

“As far as the government is concerned, it’s clear that the film industry is not a priority for them. I’ve spent over five million rupees on the production of Journey of Icons, with little concern for financial recovery. Even when the show does bring in money, a portion of it will be given to the veteran artists who have appeared on our episodes,” he says.

“The government,” he adds a little dejected, “hasn’t even recognised the film industry as an industry yet.”

Just last year, in his term as the Chairman of the Pakistan Film Producers Association (PFPA), Rasheed made tremendous strides in conducting negotiations with the government.

“We had 13 meetings with the government in my tenure as the Chairman of PFPA. Every meeting was attended by anywhere between 13 to 15 members of the PFPA — people who are the real stakeholders of the industry, and who are continuously making movies,” he begins.

About 17 or 18 members of the PFPA attended the last meeting with Gen (r) Asim Bajwa, the then Special Adviser to the Prime Minister, who was diligently trying to get the film industry recognised by the PTI government. According to the last update that the PFPA received, the government had sent a policy to Prime Minister Imran Khan, and it is on the verge of approval. In fact, they are set to announce it any day now.

Whatever the case maybe, it’s up to the people who have been running the industry until now to make sure it stays alive, Amjad Rasheed tells me, adding that he’s got 300 million rupees already invested in projects.

Rasheed, however, is agitated by filmmakers’ and studios’ egos to release all tent-pole titles on Eids. “We haven’t one single person who can make anyone understand or make the industry come together,” he exclaims.

The first step

Of the many problems the industry faces, Rasheed has a novel solution to the international box-office problem. He suggests that Pakistani films, while perfect for domestic release, should license international rights to streaming platforms. That way, it’s a win-win situation for our film industry. As things are now, very few films make money from international theatrical releases.

Amjad Rasheed says that for now he’s happy with the films that are under production and the titles he’s acquired for release. However, he wants new filmmakers to try out new things and also take a look at the past for reference. While the market is booming — Pakistani producers hardly stopped production during the pandemic — one shouldn’t forget about the people who once made Pakistani cinema great; the younger generation can learn a lot by their experiences, he says.

For the masses, the candid emotions of an interview show such as Journey of Icons would probably do the trick, and for the film students of the future, Rasheed’s digital library could prove to be a perfect resource to consult and learn from.

“This is but the first step,” Amjad Rasheed says, and rightly so. The path to a complete and all-encompassing resource is a long and hard one indeed.

Originally published in Dawn, ICON