What exactly did we lose when Amjad Sabri was taken from us?

Culture critic Nadeem F. Paracha once wrote an essay titled 'When the giants squabbled (music soared)' which examined the trajectory of qawwali in Pakistan.

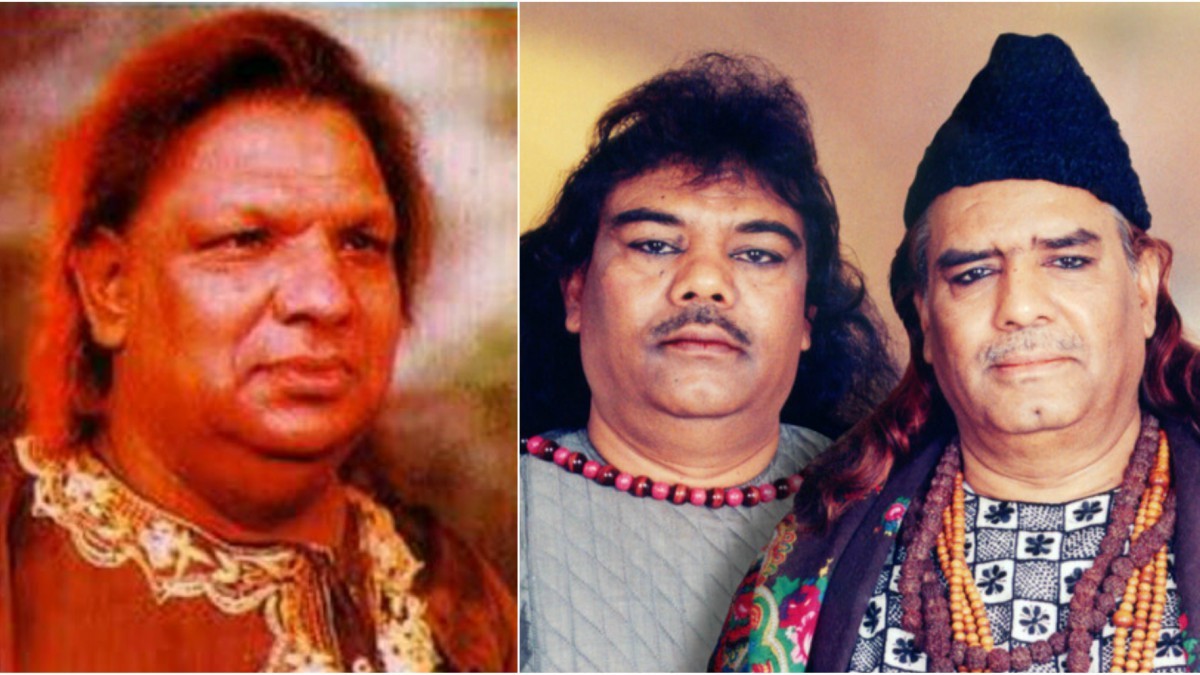

The headline referred to the artistic rivalry between the wild-haired Aziz Mian Qawwal and the urbane Sabri brothers starting from the late 1970s, which took place in the form of immensely popular qawwalis, signaling what Paracha refers to as a 'golden age' for the art-form.

It is reductive to explain this rich intellectual debate in a few lines, and one must be careful not to ascribe present-day understanding to that time. To the contemporary eye, Aziz Mian’s esoteric poetry and singing style would represent a ‘liberal’ attitude in contrast to the ‘conservative’ views and styles of the Sabri Brothers. However, that would be to misunderstand the context.

In reality, both were products of a modern age, when the centuries-old art-form of qawwali was moving away from live performances at shrines to appearances on TV, radio and records.

The country had undergone rapid urbanization and was continuing to transform itself from the old ways. In the face of this change, the approach by the Sabri Brothers was perhaps more in line with the idea of modernity. Their melodic style and accessible lyrics refrained espoused a more orthodox view of religion that appealed to their newly urbanised, often middle-class audiences.

In contrast, the critic Nabeel Jafri notes that Aziz Mian’s baroque lyrics and ecstatic style represented an attempt to criticize these new changes. In a quite brilliant essay, he writes that “[i]nstead of calling for a return to the way of life as it used to be, Aziz Mian instead used the very same urbanization as a weapon against itself by… argu[ing] that order itself is a form of oppression that must be resisted.”

Put simply, Aziz Mian wished to resist modernity through his qawwalis while the Sabri Brothers explored ways of finding compatibility within religion, qawwali and the modern world.

This was the debate that was running in my head in the aftermath of Amjad Sabri’s death.

Regardless of who actually killed him, the fact that terrorism could plausibly be blamed is an indictment of our current culture. If the Sabri Brothers had sought to critique Aziz Mian for his relative unorthodoxy back in the seventies, then within a couple of decades their own heir was perhaps murdered because the form of qawwali itself was now viewed as a heresy.

Granted this is not a majority opinion, but it is one aspect of the decade-long war in our country that has taken place in the name of religion. Whereas qawwalis were once understood as the sublime expression of Islam in the subcontinent, now the form finds itself ideologically imperiled.

The Sabri Brothers had meant for their heritage to be one that represented a more orthodox Islam, yet orthodoxy outstripped their conventions to an extent that modern Pakistanis might view them in a similar light to Aziz Mian, rather than as his nemeses.

During this time, another equally potent threat has been the ongoing journey of qawwali becoming commodified, and qawwals becoming entertainers.

It has required a reworking of not just musical compositions but also the place and nature of performances. In light of both these significant threads, Amjad Sabri’s career was one where he had only just begun to step out on his own.

His gregarious personality and musical reverence for his heritage had made him well-known, but musically his identity was not extremely distinctive. Tragically, that looked set to be changing, as he had released a few acclaimed tracks in the past few years, notably a version of 'Tajdar-e-Haram' with Shahi Hasan and Sara Haider.

Moreover, he had also completed his recordings for this season’s Coke Studio, which might have truly helped him 'arrive' on his own terms. This is not to say that Amjad Sabri’s career was insignificant – far from it. In keeping the art-form as well as the famous works of his father and uncle relevant, he had helped qawwali navigate a new world of digital media and cable TV. But the tragedy was the fact that right when the moment came for him to mark his own name, he was taken away.

The sense of loss for Amjad Sabri was reflected in the fortnightly charts, which saw a surge of Amjad Sabri’s track, as mourning fans turned to his voice.

Three of his songs come in the charts, with 'Tajdar-e-Haram' at 3, 'Mere Khwaja Piya' at 7 and 'Ali Kay Saath Hai' at 13. The advent of Ramazan had meant that there was an almost complete stop to new releases, and thus Abida Parveen’s 'Noor-e-Azal', re-released by a brand for the holy month comfortably topped the charts. The month also saw a surge for sufi music, with 'Sawali' by Darvesh (no. 9) and 'Meda Ishq' from Nescafe Basement (no. 10) doing well. The charts also have the usual evergreen faces such as Atif’s 'Dil Kare' (no. 2), still in the charts over a year after its release, as well as the indefatigable 'Bandook' by SomewhatSuper (no. 8).

Perhaps the rains were the reason Atif’s decade hold hit, 'Bheegi Yaadein' (no. 14) is also back in the charts. The two breakout drama OSTs stay in the top 20, with Hadiqa’s song for Udaari at no. 6 and Qurutulain Baloch’s effort for Mann Mayal at 17. Amongst the sort of hidden gem songs to watch out for, have a listen to Ammar Rashid (no. 11) and Farhan Zameer (no. 19) both covering Faiz, as well as indie star Shajie’s 'Sab Acha Hai' (no. 18).

Ahmer Naqvi is a freelance journalist, and Director of Content at @patarimusic.